2: Practices of Inclusion

Introduction to Buddhism00:00

At the time, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), founded by Billy Klüver, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Whitman, and Fred Waldhauer, set up a research project called American Artists in India (1970-1971). In their “brief history” E.A.T. describes the project as follows: “E.A.T. initiated a project in 1970-1971 funded by the JDR 3rd Fund for American artists to travel and work for a month in India. The following artists participated: Jared Bark, Trisha Brown, Lowell Cross, Jeffrey Lew, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Kate Redicker, Terry Riley, LaMonte Young, and Marian Zazella. They recorded their experiences with film, tapes, journals and still photographs. Interviews were carried out on their return.” ↩

Steve Paxton In the early, my early investigation, dance was a mind science in a way that it wasn't just a physical, you know, performance art. It was a…it had real questions about what a mind was and how it can be…utilized. Which is weird cause it's like the mind trying to think about how the mind works. So, it's got a kind of reflexivity that reflects itself. Reflectivity, maybe is… Anyway, so, I went to India in '711 and there I found a teacher who was a refugee from Burma, in those days it was Burma.

Tom Engels Now it’s Myanmar.

Steve Paxton Yeah. And his family had been…it was originally Indian and moved to Burma at a time when that was common and they had been successful merchants and he had studied under Burmese, a Burmese sect, I guess, of Buddhism, which claimed to have begun under the tutelage of the Buddha. And that's where they got all their instructions and with…what do you call it when you pass down traditions by word of mouth. It wasn't ever written down, but it was…

Tom Engels …oral tradition.

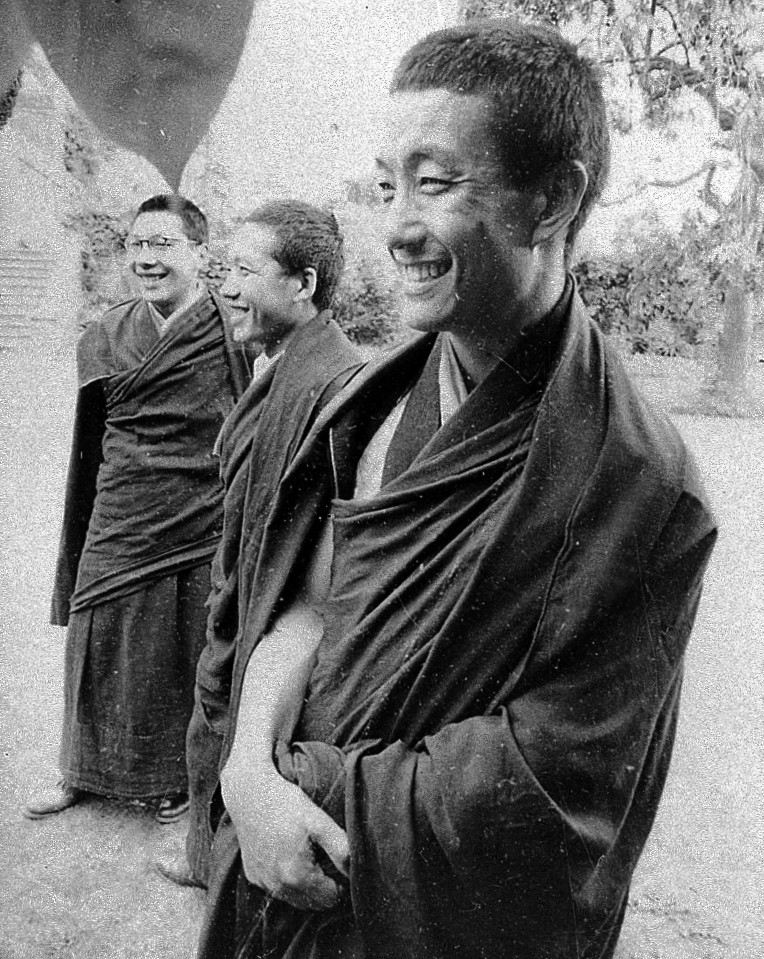

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Choje Akong Rinpoche and Jampal Kunzang Rechung Rinpoche in India, 1963, Wikimedia Commons.

Steve Paxton Oral, yeah, rote, so that tradition had been passed down to him, and the family had been ejected from Burma and come back to India and he was continuing to teach in India. And so I felt, very…first of all, I swallowed that story. You know, that the teachings were coming directly from the Buddha. I mean, I decided, how could I refute it? How could I question it? And, you know, you just might as well accept that that's at least what my teachers thought, you know. And, so I studied with him, not extensively, but about a month total of meditation retreats and, and teachings by him. And the other connection, a different connection was in the States. I was in Boulder, Colorado where Trungpa Rinpoche was teaching and I went to many of the presentations.

Tom Engels Okay.

Steve Paxton Do you know who he is?

Tom Engels No, I don't know.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987) was a Tibetan Buddhist monk. In 1974 he founded the first Buddhist-inspired university in the United States of America, Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. ↩

Steve Paxton He came to the West, wrote a well-received book in English.2 I think he studied at Oxford or Cambridge, one of those. And you know, so his level of English was extraordinary. Plus, his connection to Tibetan Buddhism…he was a reborn person. So he, as an incarnate, he had a very high position and had connection to other very high incarnates. And so, he would bring them around to give presentations in Boulder. And then there was a lot of meditating there, and I met Trungpa and talked to him and a little bit, and had friends who were very connected to him, Barbara Dilley who was in Grand Union for instance.

Tom Engels Okay. I think I've seen a documentary about him. It was released some years ago. Wasn't he first based in India? And then because of…it was Gandhi who kind of saw the, saw that group of people as almost a political threat and there was, I think, an attack committed against them. I think one of their buildings was burned down. And so he sent his secretary to the United States to find a piece of land. And that was Boulder.

Steve Paxton Really?

Tom Engels Yes. So it was his secretary… It was his secretary that was sent off with a bunch of money and he had told her, “You should only come back when you have found a piece of land where we can all move to.” So I think she was away for about a year and she found, I think an advertisement in a newspaper and someone was selling his ranch and she went and bought the land, and then she prepared the land so that everyone could move.

Steve Paxton That may not be the same story.

Tom Engels No?

Steve Paxton Because in Boulder, he was living in the city. So it wasn't…and he, they purchased buildings in the city for the school and the temple and all of that. So it may be a different…

Tom Engels confuses Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche with the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. The documentary he refers to is Wild Wild Country (2018) by Maclain and Chapman Way. ↩

Tom Engels It may be a different one, but yeah there are parallels in that time…3

Steve Paxton Absolutely. There were a number of…implants, into the United States.

Tom Engels So you were…you were frequenting those meetings, you were studying with them as well at that moment…

Steve Paxton Well they started a school called Naropa, which had a dance program and Barbara was in charge of it at one point, she went on to become the head of Naropa. But, so I was invited to teach there in the summers and maybe sometimes in the winters, I don't know, for a number of years. And so I would go and drop into this Buddhist school and its…milieu in Boulder.

Tom Engels And what would you teach there?

Steve Paxton I taught Contact I suppose. One year I taught composition.

Tom Engels Yeah. And which year we are talking about now? Because in 1970, '71, you go to India and then…

Steve Paxton I have no way to date those years. I think it was in the late seventies.

Tom Engels Okay. Yes. And Barbara Dilley was present there as well. So, Barbara…

Steve Paxton Yeah. She was a student of Trungpa, so she was there, you know, to do that. And she also had, position in the school and they had a building, you know, with a big studio. And yes, I did performances and taught there.

Tom Engels And how, if you look back, do you think there was a remarkable influence of studying with these people or being surrounded by their practices, their ways of thinking?

Mary Fulkerson was an American choreographer and teacher who was seminal in the development of Release Technique, a dance technique developed in the 1970s which focuses on muscle relaxation, gravity, and the use of momentum. Daniel Lepkoff recalls the classes with Fulkerson as follows: “In Mary's classes we worked with developmental movement as the source of a basic vocabulary. We studied and practiced rolling, crawling, walking, running, falling, and the transitions between these patterns. Mary had a system of anatomically based images that mapped out functional pathways through the architecture of the body. Up the front of the spine to the base of the neck, through the spine and up the back of the skull, down the face, through the spine again and down the back to the sacrum, around the outside of both halves of the pelvis, down the outside of the legs, down the top and outside of the feet, up the inside of the feet, up the inside of the legs, through the hips joint, up the front of the spine, and so on. These pathways indicated structurally sound lines of compression and support, and channels of sequential flow of action at work in the underlying developmental patterns. These images were considered to be ever more refinable once we were ready to perceive in finer detail. An important aim of the technical work in Mary's Release classes was to draw the body closer to channeling its action along these pathways. This would both re-align the body so that weight was supported through the center of the bones as well as re-pattern the flow of energy so that action was initiated by the muscles closest to the bodies center. This shift would release the outer muscles of the body from holding weight and free them for what they were meant to do, namely move the body. This was one reason the work is called “Release Technique”.” Daniel Lepkoff, “What is Release Technique” in Movement Research Performance Journal, Fall/Winter 1999, #19. ↩

Steve Paxton I was very intrigued with the whole thing. I had felt from before I had any information about Buddhism, an affinity with it. Just its openness and its…the possibility of working on the mind. So even before I went to New York, I was feeling an affinity with Buddhism, but I didn't know much about it. So, then I did, you know, reading and what have you. And the riddle of Zen Buddhism, you know, how it teaches, and all of that was a great interest, you know, and I knew people who were into it. And then this contact in India, when I went in '71. So, I wanted to find out more about it. In a way this reflects also how I went to England later in the 70s, and worked with Mary Fulkerson.4 Part of my motive for going was just to study her and see what it was that this new releasing technique that she proposed was actually doing, how it was taught, how it…what kind of experience it was. You know…

The open mind10:33

There is a confusion about the date of the Grand Union performance at the University of Iowa. The performance took place on Friday, March 8, 1974, instead of March 1972. Nevertheless, it shows the porous nature of Grand Union performances and how individual practices could enter the whole. ↩

Sally Banes has described The Grand Union as follows:“The Grand Union was a collective of choreographer/performers who during the years 1970 to 1976 made group improvisations embracing dance, theatre and theatrics in an ongoing investigation into the nature of dance and performance. The Grand Union’s identity as a group had several sources: some of the nine who were its members at different points had known each other for as long as ten years when the group formed. They had seen and performed in each other’s work since the Judson Church days. Most had studied with Merce Cunningham, and three had danced in his company.” Sally Banes, “The Grand Union: The Presentation of Everyday Life as Dance” in Terpsichore in Sneakers, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980, 203. Amongst its members were Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Douglas Dunn, Barbara (Lloyd) Dilley, David Gordon and Becky Arnold. ↩

Tom Engels I've been very interested in this notion of the open mind or, a physical state where you're ready, you're prepared and that that also requires a certain softness. Right? And, I was looking yesterday at the recordings of the Grand Union performance in Iowa in 19725 and6 I was so stunned by, let's say, the diversity that one sees on stage, the diversity of minds, of aesthetic paradigms, how very different aesthetic strata can exist simultaneously, whether it is…

Steve Paxton In a way that's the drama of that improvisation that particular night, I remember.

Tom Engels Yeah. I… It starts with a conversation, between David Gordon and Barbara Dilley. He's asking her questions: “Do you need a score? Do you need a choreographer? Do you need some music?” And at the same time, you and Barbara herself and someone else are developing, let's say, almost like a structural choreography of steps, trying to slowly go forward and backwards and, slowly, over the course of this conversation, which lasts I think 20 or 25 minutes, you go further and deeper in the space. And so, you have a very, almost formalist approach there. You have the daily life entering or, let's say, a non-theatrical way of speaking, having a conversation, then you have very, let's say, theatrical, dramatic acting. I don't know who's doing it, but it's a couple pretending to fight and then someone dies and there's like lots of drama. And I thought, wow, there's such a diversity, that nowadays maybe wouldn't be so thinkable. Like I don't…I don't see that kind of allowance or the permission to really enter questions from various, very different and specific angles.

Steve Paxton In that performance, the whole gynecological aspect of David and Barbara, David as the doctor and Barbara as the patient…In that particular company, at that particular time, we were very into very random pursuits in the performance. In a way, the more random, the better. The more room you found to relate to things.

Tom Engels And random as in…

Steve Paxton Random as in a fight between two people, random as in David asking about the structure of, you know, what Barbara needs, David asking her about her organs, her inner organs. There was a moment where I think she laid down and something was inserted between her legs, you know, like a kind of mirror object.

Tom Engels There's a mirror on stage indeed.

Steve Paxton And so, you know, kind of standing in for a speculum or something, but anyway, it got quite…you know, how many times has a dancer been subjected to, at least a reference to a gynecological examination on stage, you know, that's how broad things got in that particular performance.

Newspaper clipping from The Iowan Daily, March 7, 1974, ©2020 The University of Iowa.

Tom Engels Yes. And how would you deal with that yourself? Because there's so many different kinds of approaches and I assume that maybe the members not always would align with the others', let's say, visions or aesthetic preferences.

Steve Paxton Yeah, but you didn't have to, I mean, you could stay outside them. You could stay outside them and still refer to them. I felt like in that particular performance, I was acknowledging the developing story that was happening, which centered on Barbara. And, uh, she eventually left the stage via the window, which took her outside the theater, and then returned, via the back of the theater, when David called for an audition, an open audition for replacements for Barbara. Barbara herself came in to audition for her part, you know, which was a delicious…twist of the situation. So, how did I relate? Structurally I think is how I related. I was responsible for an exit which happened behind a screen that we all got behind and then maneuvered and exited the stage, you know, sort of mid performance behind. I was responsible for…I was just trying to keep up with the ongoing imaginative structures that we were evoking, and also to keep dancing occurring so it didn't turn into a drama with the text, you know, and an ongoing story only, but also that we kept up our freedom to dance or freedom to, you know, just walk across the stage or relate to each other in different ways outside the story…I can't, I haven't seen the tape for many years, so…

Tom Engels I bring this in as a specific example, but I'm, let's say interested generally in like how that worked, how all these different forms of expression could actually appear together in the same space with a set of very different people, but there seems to be as a certain trust in each other. A permission, an allowance, where you could indeed either choose to join something and align yourself with a certain action, or step out and be at the side. And I was wondering, how a performance like that would be prepared because we know that it is improvisational, but to which degree…

Steve Paxton It was not prepared.

Tom Engels Not at all?

Steve Paxton Not at all.

Tom Engels Okay.

Steve Paxton I mean, maybe others did prepare. David had a…he sometimes prepared extraordinarily. I remember a performance in which he appeared in full Kabuki makeup. We had no idea he was going to appear this way, and I don't know exactly what he did in that makeup. I don't know how long it lasted, but because I had been on stage for the opening and David didn't appear until…I saw him in this full Kabuki makeup, you know, only as I was leaving stage. And so, I don't know, I went down to get another costume or something and I didn't see what he did. But he obviously…

Tom Engels He had something in mind, yeah.

Steve Paxton He had something in mind and…but I didn't, and sometimes I arranged it so that I arrived at the performance at the moment the performance was supposed to start. So, there was no way to collaborate with anybody before it actually began.

Tom Engels So even like the objects that are present on stage, like a bunch of chairs, a piece of cloth that you use - remember? You have a fan and you have some piece of fabric in your hand and mouth.

Steve Paxton I don't remember.

Tom Engels It's very beautiful. So that's why I thought there must have been some sort of preparation because it's as if it's not improvised at all.

The Grand Union often had residencies at universities in which they would offer a combination of presentations of Grand Union’s work, individual work, and the teaching of classes. The “company narrative” in the National Endowment for the Arts report reads as follows: “[…] The six dancers/choreographers (Trisha Brown, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, Nancy Lewis, Barbara Dilley, and Steven Paxton) are all experienced teachers. The group can provide classes in several of the established dance techniques; more important, they have developed their own classes to promote insights into movements, its physical roots and potentials, and composition. The Grand Union hopes to offer students the opportunity for stimulation and utilization of their own individual ideas for movement, and for development of an awareness of themselves and others in performance. Classes should be limited to 20 or fewer people except by special arrangement.” U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, Dance Touring Program: Directory of Dance Companies, Fiscal Year 1976, 90. ↩

Steve Paxton One of the performances at Oberlin, which is the time that I did Magnesium and all of that, that residency7 there, there was in the basement of the building…I was staying in a building that was a sports building. So, in the basement of that, there was a huge wrestling mat, very heavy. I arranged for that mat to be brought to the back of this theater and dumped during the performance. Nobody else knew this was going to happen. I started asking for that mat. From the audience, I started asking for that mat to be moved over the heads, you know…

Tom Engels Oh wow.

Steve Paxton …of the audience and all of them, you know, like moving it toward the stage and got up on the stage. And so I had, I don't know, probably 10, 15 minutes of encouraging the audience to do this move and they were perfectly willing to do it and…

Tom Engels And together it was possible to move the mat?

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah, yeah. And that was, at least for that moment, the spirit in the house was the audience very willing to collaborate and to do, you know, things if we asked them to. But nobody else knew that that was going to happen. So there was a whole event, you know, massive event in the theater. That was a surprise. But I did prepare it. I did have to move the mat to get it there. I didn't know exactly what I was going to do with it.

Permissions22:34

Tom Engels Did you ever feel that there was some kind of tension created within a group, let's say, when you asked the audience to move the mat and it takes like 15, 20 minutes of the whole performance…

Steve Paxton 10 I would say, let's say 10.

Tom Engels Okay. So that also means that basically you take all the attention in that moment where there was…how would you deal with that in a group with people bringing their own things? Were there tensions or was it extremely permissive?

Steve Paxton It was extremely permissive. I think we tried not to step on it if an event had arisen, you know, say in that same performance earlier on. There was a duet between Yvonne and David on a piano, on top of a piano, an upright piano, which was being played by a student. So there was good light on that. There was a spotlight. It had been arranged. David had arranged that, and he was singing songs. He was lying like a singer in a bar, you know, he was, you know they sometimes sat on the piano or something. He was taking that image. And so he was lounging on top of this piano and Yvonne got up there and started lounging on him. And so it was like a stack of performers, and he kept singing. And the pianist kept playing, and Yvonne kept, you know, almost falling off. Really surprising that nobody got hurt in that bit, and it went on for quite a while and I wouldn't have thought of interrupting that. Although at a certain point, such inventions tend to sort of peter out, you know, they sort of lose their energy and they don't have any place to go beyond where they've established, and then it's, you know, appropriate to introduce new material. Let them find their way again or…let it fade away, or whatever needs to happen.

Tom Engels But that's what Myriam and I were so stunned by yesterday because what you see is, for example, an action happening in front, and something's happening more in the periphery, and somehow these elements all of a sudden merge or they swap position or…there is something so almost natural about how elements shift in space that we were almost convinced that there were, let's say, agreements made before…

Steve Paxton No.

Tom Engels …because it's so meticulously done. And that's why I brought up that notion of the open mind…

Steve Paxton Well don't forget we were all practiced dancers, everybody in the company was a practiced dancer. Everybody had been, you know, we were all mature in theater. So it isn't that difficult. In fact, I think every improv theater in the country would say that it's pretty natural to be able to…figure out what elements are strong in a moment and which ones are weakening and which ones, you know, might come forward, even if they're abstract, you know, after something dramatic has happened, you know, a clear situation between Yvonne and David on top of the piano. To let that, to let something else come forward and start inventing, you know, with a new element. It's just very easy. It's a little bit like playing.

Tom Engels [laughing]

Steve Paxton Did you ever play as a child, imaginative games with a friend?

Tom Engels No?

Steve Paxton You didn't?

Tom Engels Imaginative games?

Steve Paxton Yeah. I used to have a friend, a girl. We lived on opposite sides of a vacant lot. So, in this lot there was a tree and that tree was one of our basic play things, you know, we would climb up in the tree and she would say, “Okay, I'm going to be a princess.”

Tom Engels Oh like that, yeah, like role playing or…

Steve Paxton Role playing.

Tom Engels Yes, yes of course, this I did as a child.

Steve Paxton But you have to invent your armies. You have to invent your clothes, you have to invent, you know, all these things that you establish as a reality for the game.

Tom Engels Yeah.

Steve Paxton Maybe realities. The premise of the game. Yeah. So it's a little bit like that. I mean it's a very basic human ability.

Tom Engels And nonetheless it's not so obvious to share that imagination with someone else.

Steve Paxton If you're all improvising together and you go out on a stage, you agree to go out on a stage in front of an audience and you have no material except your training, and your understanding of each other. Then it is unusual. I think you remarked, uh, at some point maybe in conversation about a grant that Grand Union got…

Tom Engels Yes, exactly.

Steve Paxton …with me as choreographer, which I did not propose to the national endowment, but David and Trisha had put forth this grant in my name. You know, as though I had submitted it and we had gotten some money and…I sort of lost my point here…what was that point?

Tom Engels The endowment. The application for the endowment.

Steve Paxton But before that, there was some reason that I brought this up.

Tom Engels Yes. You were talking about…trust, the trust in each other. There's no material, the image, the game, playing the imaginative games. How to share that with someone else, how unusual it is…

Steve Paxton Oh, oh, oh, oh. We were an improvising dance company. The grant that was put in to the national endowment was for a choreographer because there was no money to…for us to pursue what we were really doing. The only money was for, you know, was for a structural choreographer and company thing. So that had to be invented in order to get the grant. And it was a lie. But on the other hand, it was…we just…we were summarily rejected as improvisers. That was not at all a possible pursuit.

Tom Engels Pursuit.

Steve Paxton So we had to do something else. And wind around the rules.

As a response to a review by Robb Baker of a Grand Union performance, Yvonne Rainer wrote the following to Dance Magazine: “A misconception has dogged the step of the Grand Union since its inception. Namely, that the Grand Union is Yvonne Rainer’s group or that Yvonne Rainer is the director and/or pivotal figure in the company. ALL UNTRUE.” Yvonne Rainer quoted in Margaret Hupp Ramsay, The Grand Union (1970-1976): An Improvisational Performance Group, Peter Lang Publishing Inc, 1991, 43. ↩

Tom Engels It's very interesting because I stumbled upon this, let's say statement that Yvonne Rainer sent to…maybe it was the Drama Review.8 I don't remember the magazine where she explicitly stated in response to a review that had been written about Grand Union, that Grand Union was not her company. Because I think in the very beginning when the Continuous Project shifted into Grand Union, in some reviews people spoke of Grand Union as Yvonne's company. And so on the one hand, the choreographer that it is publicly attributed to, has to publicly announce “it's not my company". At the same time, you amongst yourselves have to invent strategies to, let's say, put Steve Paxton as the choreographer of a piece, but obviously there were other people that had a shared, let's say, creative directorship or a choreographer's role.

Steve Paxton I mean, I didn't put the grant forward. I didn't know about it until after it had been submitted. I was not told that my name was being used in this way. So…but it was all right. You know, and I actually think, I think the work of the Grand Union had something to do with loosening up the granting attitudes toward…you know, now there are people who are dance improvisers and that's what they do. And I think that's a bit of the legacy of Grand Union there. You know, a new reality was included in the premises of what dance and choreography could be.

Magnesium33:48

Tom Engels At the same time, you already mentioned it, in 1972, there's the residency in Oberlin college, and you're teaching a workshop with a group of men which results in Magnesium. So you come as a group, but you also start to teach your individual practices and things start to also develop apart from, let's say, the common project that Grand Union was. In this piece that we saw before, in '72 in Iowa there is a duet with Alex Hay that you're dancing.

Steve Paxton Alex Hay?

Tom Engels Yeah.

Steve Paxton At Iowa?

Tom Engels Yeah.

Steve Paxton No, he wasn't there.

Tom Engels He wasn't there. Then…

Steve Paxton Alex Hay was a part of a much earlier…

Tom Engels He has blonde hair.

Steve Paxton Douglas Dunn.

Tom Engels Yeah, it's very difficult to see.

[TE shows some stills on his computer screen]

Video stills from Grand Union performing at the University of Iowa, March 7, 1974.

Tom Engels This is you, I suppose…

Steve Paxton Douglas Dunn.

Tom Engels Douglas Dunn. Okay. And all of a sudden you see, let's say a first, maybe it's not the first, but you almost see the very first steps of Contact entering.

Steve Paxton It's precisely in a duet with Douglas Dunn that I had the sensation that I pursued as Contact Improvisation. I would be interested what performance did we just glimpse there?

Tom Engels That was the one in Iowa. 1972.

Steve Paxton That was Iowa.

Tom Engels And so you see, I think it's minute 30 of the show.

Steve Paxton By 1972 I had already…I had already started Contact, hadn’t I? Or was that…

Tom Engels Yeah. So this was the show in March.

Steve Paxton I had officially started, maybe I hadn't worked it that much.

Tom Engels This was the show in March. It's the beginning of '72. But you see these two bodies colliding, trying to support each other. But you see that it's still a testing ground. It's a laboratory. Then I had the same feeling looking at Magnesium, where you see the attempt of swinging people around, but still using the hand, the grip holding each other's wrists, testing a pivotal force, people falling into each other. But there's also still the mat present, which also highlights the notion of exercise. There's still a sports element to it. And I bring this up because I'm interested in how all of a sudden there's more individual practices that start to crystallize themselves, and I was wondering how you were dealing with that, how you let Grand Union exist parallel to the very start of Contact. If there were some, let's say, cross-fertilization of these practices or whether it was for you really the start of, let's say, going astray, like something new had started, which you would develop. And also let's say surround yourself with a bunch of new people that you would…

Steve Paxton Develop the material…

Tom Engels …develop the practice and material with.

Steve Paxton Well, so, let me see. I think in the Iowa performance, Trisha had already left the company. I think Yvonne had left the company. Is that true?

Tom Engels Yvonne…

Steve Paxton Was not in Iowa.

Tom Engels It was in 1972 that she kind of withdrew for the first time and then she reappeared later, but she was not, let's say, a permanent member.

Steve Paxton Yeah. And so what was happening as far as I could see is that out of Grand Union, well, one way to look at it, out of Grand Union, so much was explored and…discarded after it had been initiated that people got ideas that they wanted to pursue. Certainly, that was true for me with Contact Improvisation. You know, as a part of that residency, I felt Magnesium was an attempt to articulate something but it wasn't quite right. And what I felt was that it was dangerous. You know, the level of energy that we were playing with, you know, it was all young men. They'd had three weeks training, you know, they were…I had to assessed them, as the leader. I had assessed their ability to remain stable in a high energy situation, you know, with falling, and rolling and all of that. They weren't going to become disoriented. So, we'd gotten that far. But then the actual premise of the touch didn't develop until…well until I had reflected on that performance and thought about things like Aikido and its use of touch and the duet with Douglas Dunn. And so to refer back to something we said earlier about dance as a mind training, what I found in that duet with Douglas Dunn was a way that he and I were working in which we were both following the other. This was not a thought I had had before that. So first I had this sensation, then I characterized it and I said, okay, we're both active, we're both responsive, but we're neither one of us leading. So given the fact that we were already engaged in a kind of duet, you know, physical touch in a duet, at the point where I felt that sensation and identified it, it was a bit of a revelation as a possible connection between people. Now here we're having one just like it in conversation, you know, it's not unusual in conversation, but in touch, you know, in physical terms, when would you have it…in sex you have it maybe. In good sex. Well what I call or think of as good sex. Or just companionship. Or if two people are trying to climb a tree or climb a cliff or something, they might give each other physical support, but then it's very much aimed at a goal. But this was not aimed at a goal. This was the touch. This was the attitudes. You know, each supporting continuation of the event with no leader, neither one of us stepping into a, now we have to, you know, achieve this height on the cliff or something, you know…

Tom Engels But it's remarkable that you seem to both understand it.

Steve Paxton Yes.

Tom Engels In the moment it was happening.

Steve Paxton Yes, that's what it had to be, that's what it had to be. I had to think, at least, that he understood it in the same way I did and that he was not leading in the same way I was not leading. We were both willing, you know, we were both available, but neither one of us was saying what to do. And there was no goal. All of that was needed to reveal the sensation to me.

Tom Engels Yes. You said you felt that Magnesium was an attempt, but it was too dangerous. Does that mean…

Steve Paxton Yeah it was a bit dangerous.

Tom Engels Was that then also the only time that Magnesium was performed or was this a piece that you would tour?

Steve Paxton It was the only time it was performed, and people have asked to revive it. Yeah. And I've not been enthusiastic, because I found my way with those men to a place where we could get pretty dangerous and it seemed okay. With a different cast and with a different director who wasn't…who might have been more interested in the choreography of the situation rather than the training to get the situation to be possible, you know, or just somebody with a different…I feel lucky to have gotten that performance and to have not gotten any injuries out of it. And so I've been reluctant to allow it to happen again, you know, as a revival. If they wanted to do it themselves, they can do it.

Tom Engels They can do it.

Steve Paxton Yeah. But it's not, you know, I can't give permission.

Tom Engels To me it was remarkable how on the one hand, indeed there is this colliding of people, there's a certain sense of danger and at the same time there's very strong counterpoint created by the very end, which is everyone standing still for quite a while.

Steve Paxton Five minutes.

Tom Engels Five minutes. Could you say something about that standing still? Is this already what you have called later the small dance or…

Steve Paxton Yes.

Tom Engels Was that…that was already conceptualized at that moment?

Steve Paxton Yes.

Tom Engels Yeah? Okay.

Steve Paxton And it was part of the training. And it continued to be part of the training because I wanted to expose the students to the highest activity that could safely be performed, which later I think in Contact Improvisation with a lot more firm grip on what constituted training and how to assess students in their problems, you know, with orientation, we got quite extraordinarily high activity safely performed. Really I've seen just in Contact duets some of the most remarkable extremes of high energy, you know, between two people willingly engaged in and improvised and, you know, people really swooping up as high as they can be lifted and going to the floor, directly to the floor from that position and safely rolling and tumbling and, you know, not hurting each other at all. So I've seen that. But at the other extreme is what is the tiniest sensation that you can find in the body? What are the smallest elements of movement? So that the glamour of high activity, you know, which always gets everybody's attention is contrasted with an underlying minutia of sensation. And so you always have both things going on, and the minutia is not ignored. And the minutia is in every gesture of a hand, or twist of an arm, or a thrust, a little, little thrust of a leg, or giving way to weight, or all of these potential changes, as a kind of…well it's an orchestration, from the quietest to the loudest parts of a symphony, like how to keep the quietest part of the vocabulary, the most subtle, the most basic elements of time and energy.

Tom Engels I think you should tell me when you want to take a break.

Steve Paxton I know. I'm happy talking.

New North, Old South48:57

Tom Engels[laughing] Because what I think you described now is a certain relationship to micro and macro, or the interior and exterior, what is happening, movement that is sensed inside and maybe not visible from the outside or the other way around. But at that time, by then you already have moved to Vermont, to Mad Brook? You're living here already?

Steve Paxton '71 I came here first.

Tom Engels '71. I was wondering about that, let's say, a more political slash ecological mindset that was present at the time as well. But I was wondering how that decision took place, to all of a sudden leave the urban environment to actually radically rethink a daily life. How to position yourself amidst, I mean, we see it here outside, amidst a very vibrant environment, although it has another vibrancy than, let's say, New York City. But there's a lot of energy, and how to deal with these forces. So was this a decision that all of a sudden came about? Or had there been already some sort of flirtation with thinking ecology before in the years before you moved, or were there friends that inspired you? I'm just curious how that all of a sudden happened.

Steve Paxton Well, at that point, I had lived in New York for 12 years and I had found my way from being a student into dance companies and dance affiliations, but I was very poor. There was not…I was not doing something that there was any salary…Grand Union was, or we got paid for performances and we got travel paid for, but there wasn't money outside of the actual performances. So, there was nothing sustaining me. And so I was very poor and I had lived in New York, in the very cheapest of apartments. So, very bad situations. I mean, I liked them. A young man can put up with a lot, you know, I had no social pretentions, or even hopes of…I just wanted a place to put my body when I wasn't dancing, you know? So I had that. So I was now at the point, in 1970, when I first came here and visited here, I was living in a very small apartment on the top floor of a building. It was two rooms and you know, a bathroom and an everything else room. And I had a performance in Montreal, and I decided to come and visit here. Deborah Hay and David Bradshaw, whom I knew in New York, had moved here at that point. So I dropped in and stayed for a week, and in that week made friends and decided to come back. And in the autumn I came back and helped build the house up the hill. Not very well. I mean, I wasn't a carpenter, but I was there to do it and…yeah. And so that period, that second period, was a fairly long period and involved living in the main house with about 20 other people, who were the only people here. And there was no telephone to make a phone call. You had to drive to the nearest public phone about five miles away. There was no…there was electricity, there was water, there was wood heat, there was a lot to do. There was gardening, you know, we were…it was agreed that we were going to eat vegetarian. So, there were big gardens opposite the main house, and a big freezer, and…oh, and great meals every day. Dinner every day. I can't remember a bad dinner. I cannot remember a bad dinner. It was just remarkable. They were just delicious vegetarian meals, you know, from a…fresh from our own garden, you know, in the autumn. And the group here were leather workers and woodworkers and craftsmen, and they had really nice products, you know, really well constructed, well-crafted wares. And so they had a kind of…I admired them for that, and I felt comfortable with them because I felt like their work with crafts and my work with arts were similar, had similar foundations…creativity. And, so then I had formed a relationship with this woman, and I was given an invitation by Experiments in Art and Technology in New York, with whom I had worked to go to India. And so, I took her to India, we went together, and she stayed for a couple of months and I stayed for six months. Got into the meditation and generally moved around India, mostly the North and Western parts.

Tom Engels So does that mean that you actually…because…let me put it differently. At the same moment, a lot of people are doing something very similar, namely, they're leaving the cities and they're going to the land. Was this something that you were aware about at the moment…

Steve Paxton No.

Tom Engels …or is this just mere coincidence that you actually, by knowing Deborah Hay, who was living here, that you ended up here and then by experiencing the environment you decided to stay.

Steve Paxton My introduction to the “back to the land” movement was by coming to visit people who had actually made that decision.

Tom Engels Okay.

Steve Paxton But I think I emphasize how appalling my conditions were in New York. You know, these bad apartments and bad neighborhoods and all of that. I came here and the first week that I was here, I experienced a peacefulness, almost a bliss that was remarkable. It was just so…this land spoke to me very deeply. It's beautiful land, but mainly it has a lot of running water. It has a lot of brooks and springs. Now don't forget that I was raised in a desert mostly, and this amount of running water is paradise for somebody who has been raised in the South West.

The Mad Brook running close to the lands of Mad Brook Farm, 2019, Tom Engels.

Aerial view from Tucson, Arizona, 1978, photographer unknown.

Tom Engels Dry land.

Steve Paxton Yeah. It's so dry in some of those lands and the drought was very heavy on my family at that particular time. My father was trying to farm and he had seven years of terrible luck with rain. And so, that's not an unusual drought in Arizona, you know, and then, then we moved, at the end of my time in Arizona we had moved to the desert. Now when you fly into Tucson, Arizona, one of the things that's remarkable to see is that in many neighborhoods, behind every house there's a swimming pool. This is in a desert. Ordinary people can afford swimming pools. And indeed it's a kind of, you know, big part of the social life of a family, you know, a swimming pool, grill, you know, outdoor life, warm weather, beautiful nights, not much rain, you know, just the outside, you know, your yard becomes another room. With a swimming pool! And so you see all these little blue spaces behind the houses and it just seems crazy because there are so many of them, you know, you know how dry it is. You know…I'm not sure where that water comes from. Tucson, Phoenix, you know, all the desert towns of that era, you know, from the 50s onwards, you know, after the United States got its economy going again, towards the public sector. Just…yeah, lap of luxury even in miniature, you know, it wasn't mansions, it was small houses, but it was swimming pools and it's a lot, a lot of water and that water is very valuable and the air extremely dry, and the lakes in Arizona are mineralized, so you go swimming and you come out covered with salts, you know, and you need to actually wash off again with fresh water to get the lake water salt off. Things like that. So, to come here and to have…to live in a green world with a blue sky and with the brooks running was a very big, you know…I felt a very big connection with the land. You know, this…a kind of… Well, I guess New England, you know, comfort, beauty…I hadn't yet been here in the winter, you know, starting in May, is when my first encounter with this farm…

Tom Engels The comfortable version.

Steve Paxton Yeah. It's the Eden-esque season of the year.

Tom Engels Yeah, yeah. I think it's remarkable that at the same time that you're developing new skills, Contact Impro is at the very beginning of developing, you're busy with Aikido, with Zen, with yoga, you also move here to an environment where your body is also exposed in a different way to elements compared to…

Steve Paxton But I was 30 years old, approximately. You know, I mean, that's an age where one does, you make fundamental decisions around one's life. And I definitely had never admired New York City. I mean, you talk about it as the greatest city in the world, but the operative word is city. I mean, that's American's view of it anyway. The greatest city…we have greatest in the sense of biggest and most expensive etcera. Most powerful in many ways. But, I knew I had to be there for dance education and that was…there was no other place with any reputation. At the same time, it's a real sore on the face of the actual landscape. And I was aware that America had been built on the backs of indigenous people and blacks, multi-million animals slaughtered, you know, herds of bison in the Midwest. So I was…I was sensitive to all of that, and I felt like being here was a way of avoiding the worst of humanity's efforts to civilize itself.

Tom Engels But what I was hinting at is that at the same time that there's a transformation in, let's say, re-skilling your…development of skills in your art making, there is also maybe a re-skilling happening in how to…

Steve Paxton Yeah, I was 30! That's what I'm telling you. I'm telling you, this is what happens. How old are you?

Tom Engels 29.

Steve Paxton 29. So you are in that era of astrological imagery. Which is called a Saturn return. Do you feel different than you did when you were like 26?

Tom Engels Yes.

Steve Paxton Yeah. I mean, I had a depression at 27. You know, I had…I went through some real mental turmoil. I also was recognizing that I was not supporting myself very well in New York, you know. I mean, I was eating, I had a roof over my head, I had clothes, a few, I didn't have, you know, didn't have any…I had a poor life, but a rich artistic life. So that's all I cared about. But coming here, a lot of the paradox of a city, a modern city, you know, the fact that it doesn't know what to do with its sewage, and its waste, you know, the fact that it is just such a generator of pollution. Here, I felt like I could get out of that system. I could be someplace, find out about a place that was much more alive than the desert I had grown up in. I mean, I love deserts, but this place was green. Green was something you saw only, you know, in a few parks in my childhood. Artificial…artificially maintained highly desirable landscapes, you know, golf courses and parks, you know, within the city. No place outside the city. The water was not clean. Here you can drink water from the lake. Here water is soft. It feels great to the skin. It doesn't dry on your skin and make you feel like your skin is cracking off. So this place was very beautiful to me. That's this farm. And I definitely was in a position of having very little and therefore being very free, you know. I think I moved up here…I had a VW bug…I think I and my cat…

Tom Engels You had a cat?

Steve Paxton I had a cat, and all my belongings came up in that one VW bug: clothes, tools, you know, furniture, whatever I had was in that one very small car. So that's what I had and that's what I came up with and that's what I began life here with.

Tom Engels I guess in contrast to the city where things are, let's say provided for you, there's here another sense of being way more hands on, do it yourself notion of being self-sufficient.

Steve Paxton That was very much the ethos of the farm. There was…it wasn't a place where you got a lot of help. In the early days, at least I didn't, you know, have a lot of no, and if you think about it, you realize that to have some form of communal socialism, you know, where people were really helping each other and getting in each other's lives that way would weaken the whole structure. The strongest structure we could have is if every member of it were strong. So there was not a communal car, for instance. It would've been very easy to go that route, you know, and have a car, but people were suspicious that communal property was not cared for equally by all the members. And I think we saw that. We saw that actually we lived through it…how much people were willing to work for the good of the group.

Practices of inclusion1:10:05

Tom Engels It's interesting because at the very same moment, a little bit before 1968, the Whole Earth catalog starts to be distributed.

Steve Paxton Yes.

Tom Engels Which supports the belief that one has, one has the potential to learn certain skills and by applying those skills, one can actually cause transformation. Were you aware of that document at the time or, did it influence your thinking, your life…

The Last Whole Earth Catalog: access to tools, cover image, Stewart Brand, Portola Institute Inc., Penguin Books Ltd., 1971.

Steve Paxton I ordered things from it! You know, yeah, you could order these goods, you know, it was a catalog and…of a lot of things that you needed for homesteading or, I don't know. Things like churns for making butter and tools for gardening and, yeah, manuals for mechanics, you know. All kinds of books…and what entrees into further research, you know.

Tom Engels We talked a little bit about it before in relationship to Buddhism, which is very much about, at least the strand that I know of, is about self-control. It's about perceiving true nature. But at the same time you're also busy with Aikido and yo[ga]…

Steve Paxton Before that. Before Aikido.

Tom Engels It's translated as “the way of unifying with life energy.” There's also the practice of yoga, which etymologically would relate to yoke, to concentrate, to attach and to join, which I all kind of see as certain expressions of thinking in an ecology. In yoga, I think it's thinking equanimity between…chakras. So, within yourself and by finding equanimity there, you can find equanimity in relation to the world. With Aikido there's some things, it's not similar, but you…there is a notion of not being aggressive to the world, but you deal with the energy that is coming towards you. So you don't aggress but you redirect, you use the energy that approaches you. Do you think that there is a certain alignment between these practices and, let's say, ecological thinking? Did the life here…did these practices influence your thinking of life here at the moment or were these things separated for you? Were they interrelated practices?

Steve Paxton Well, the study of all of these practices suggests inclusion, and any mental study that you undertake, you know, be it music, be it mathematics, be it Aikido, suggest that you want to influence your growth or influence your development. And all of them will have various influences on you. All of these different studies and you might study many of them, you know, in a life. But for me, I think the fact that I studied dance with an attitude that it was as much a mental development as a physical, and then found Aikido and studied that and found it very helpful in many ways, but mainly the contrast between dance technique and Aikido technique. You know, what was included as a premise, you know, one to make art, one to relate to aggression. And also, the psychology in both. You know, it takes a lot of training to become a dancer in a company. You have to have certain skills, like memorizing movement, you know, like remembering relationships in space. Like, you know, things…

Tom Engels It takes 10 years, said Martha Graham.

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah, yeah. It takes 10 years, or it takes a long time anyway. It takes at least two years to kind of get your head around the basis of a technique. And then after that you have to grow the technique into your body so that you become somebody whose growth has been developed by that technique, which is what all the techniques seem to require. You know, like ballet for instance, turns out a body, they start very young, and it turns out a body that's quite unlike a normal body. It's really a different animal, different tribe…anyway, so, all of that training, to have the contrast between two of my major studies was informative, you know, like; Oh, this is a whole package, you know, dance and the company I was in is one whole package. There is another whole package premised on conflict, but a certain response to conflict, which is a peaceful response to conflict, which I thought was very beautiful, the way it's positioned. Yoga, you know, is a lot about integrating yourself, and consciously, so engaging the mind in integration with the body. Tai Chi, same thing. Aikido, you know, the premise, if in yoga you're dealing with multiple chakras and Aikido you're dealing with one, essentially the root chakra and its connection to movement and to the geometry of movement. Yeah, so all of these things are very useful, you know, in terms of getting a rounded picture of what a human is. I was still at the, at the time in '61, I started off making quote “dances” that were about walking, had a lot of walking in them. And I did that for a decade and get 10 years of walking material. So then I changed, went into improvisation and the various branches of that that I worked on. But I still kept…I still had this fundamental question about walking. And in '86 when I started working on Material For The Spine, I think I finally found a way to identify or picture for myself what walking is. So that my mind finally, after all those years and after many attempts to work with walking and trying to find out what walking was, maybe I was just incredibly slow, but we're talking 25 years later, you know, suddenly I…it came to me that walking was a matter of two spirals of the body, the right and left half of the body, spiraling around each other in a kind of rhythmic repeat. And that was…that was the combination for me of something I had been looking for, which is how to find fundamental energies and structures in the body. So you start as a neophyte in any of these endeavors. Didn't you say something about yoga being a matter of…

Tom Engels …equanimity.

Steve Paxton Equanimity… But also opening? Maybe it was Buddhism. Are we talking about…

Tom Engels As perceiving true nature. I attributed to…

Steve Paxton Yeah, okay, so…

Tom Engels And yoga was also to attach, to join…equanimity, to attach, to join and to concentrate, to yoke.

Steve Paxton So that sounds like just the discipline side of it, you know, as a definition. But there's another element of it which is to open. What does that mean? What, what it suggests is that human beings are fundamentally closed or incomplete or self-deceiving or…anyway, they have quite a ways to go after they achieve physical growth, you know…take over their own lives. They then have this next leap to make, which is to open to something beyond their own ego and beyond their own awareness and upbringing and family and society and all of that, that there's a lot of space, you know, to continue to expand into. I've heard of yoga being called a way to train the self or to stop being suppressed by the ego or, you know, a lot of generalities which suggest that the yogis think that you get to be 18, 19 years old, 20, you know, you're an adult, you're grown up, you're able to have relationships that you want and you know, find your own way in life and all that. But you haven't even started to train the mind to look at the mind. And so, that's very interesting, that there's these so-called mental experts, you know, meditation teachers, Zen teachers, yoga teachers, and they all sort of think the human being has potential that they are not able to…that they may never be able to fulfill. So…I don't know. So I think that was an underlying question through all of that part of my life, including coming here and being with other people who were obviously aware of those kinds of things. Nobody was a disciplined meditator here. Nobody was disciplined in any religion and disciplined maybe in their craft, you know, and maybe in being kind of clever about adapting to this new…because they were all city people. So if they were, they were all…I may have had as much time on a farm in my earlier life as any of them here had had, you know. But they were…they figured it out, found out what they had to know. But all of that is about opening, and all of it is about…and so your earlier remark about coming here and also coincidentally working on Contact Improvisation and Grand Union and you know, all these things, that was all about how to find out more, how to…

Tom Engels …open up.

Steve Paxton …open, you know, I mean the word improvisation for instance, I really didn't know what it meant and I kept aware that I didn't know what it meant, it's a little bit like, I kept aware that I didn't have cracked what walking was, you know.

Performance of Steve Paxton's “Afternoon (a forest concert)” in the woods near Billy Kluver's house. Photograph Collection. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York. Photo: Unattributed, 1963.

Tom Engels I think that sense of opening actually is present already from very early on in your work. I've been looking at one of the first pieces where there's the presence of animals. You have rabbits in Title Lost Tokyo, you have chickens in Jag Vill Gärna Telefonera. There's another chicken in Somebody Else. There's also a dog appearing. I wrote it down in Some Notes on Performance. In Afternoon Forest Concert in '63, you go into the woods, you dress the trees in the same way that you're dressed yourself into costumes with the dots. You're dealing with the inflatable tunnels, the plastic in Music for Word Words or Physical Things. And I thought like, there is already in all of these instances, elements entering that are to certain degree unpredictable. There's a certain behavior of otherness. So and to think that through that kind of openness that you were talking about or inclusion, it also means, to allow elements, whatever their nature is, whether they're animals or whether you talk about materials or also other people on stage in terms of improvisation maybe, to allow things to be, to let otherness be, to include that, no matter what their behavior might be. So inclusion might also mean to let go of some sort of controlling nature, to want to restrict something, to a certain kind of behavior, but to let it be. And I was wondering if I, when I'm…of course when I see you dressing the tree, I retrospectively start to think of ecology or the relationship to animals. Like here in the farm we've been talking a lot about animal behavior, how they appear, disappear, how the pigs play with each other, et cetera. And I find it striking that even maybe when there was not really a clear thinking of ecology yet, that actually it was already almost like an echo from the future, you know, like, that the thinking of environment was very much there, I think. Would you agree with that?

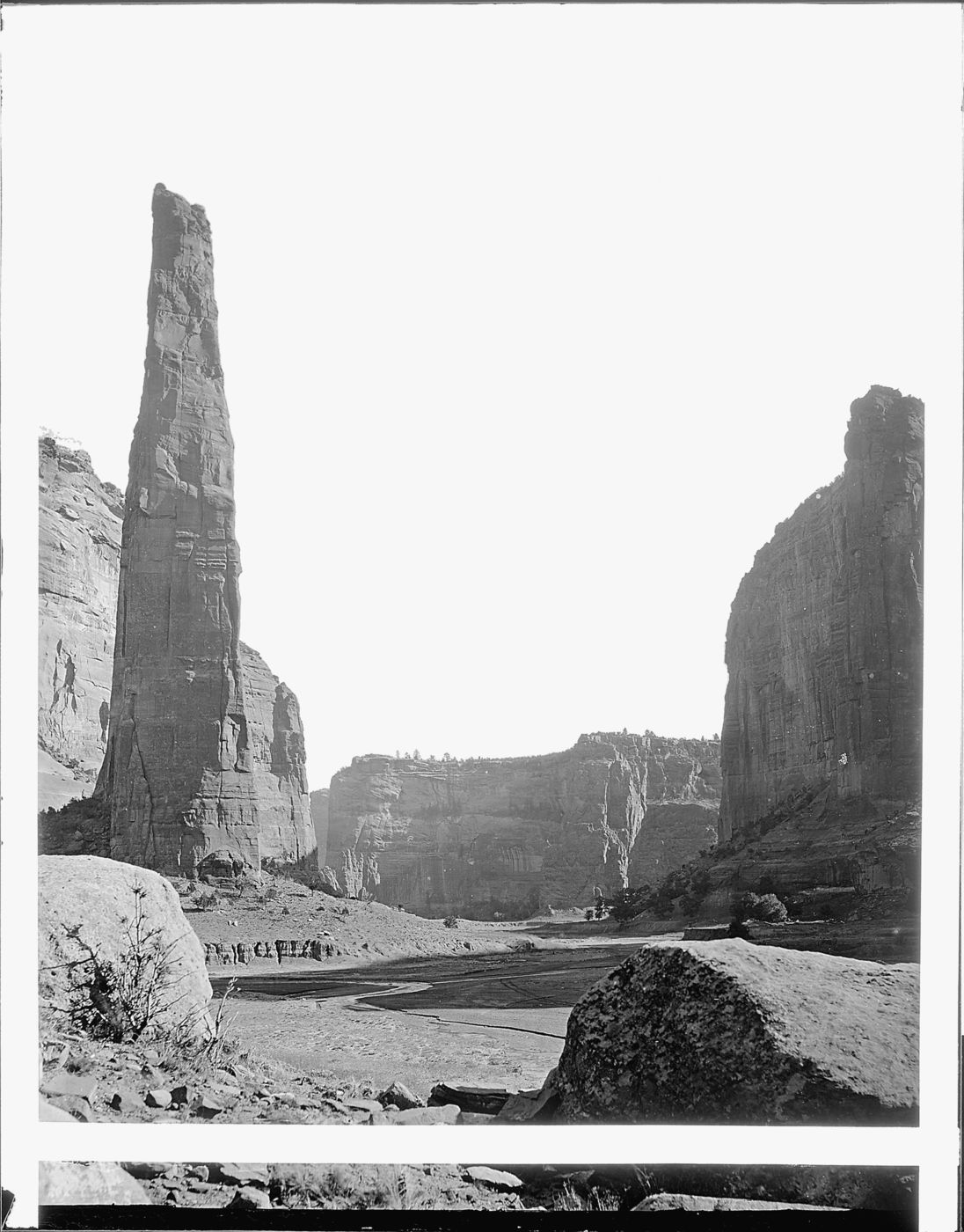

Canyon De Chelly, Arizona, 1871-78, Wikimedia Commons.

Steve Paxton Well, early life involved, at various times, living in a lot of different landscapes in Arizona and one of them being a farm in which my brother and I were of an age where we could be left all day by our parents to just, you know…there was a house, there were fields. Beyond the fields, there were woods and wilderness, you know, dry, a little bit dangerous. But we were trusted to survive. You know, even at what age…I guess eight or nine, you know, trusted to spend all day by myself and a lot of wandering around. So, I guess I made alliances with nature, you know, as I know, I'm very fond of a certain kind of rock, big boulders to climb on. I'm very fond of the Arizona granite. I know that I have this memory of being on a picnic, on a mountain side in Northern Arizona and climbing the cliff. My parents just would let me climb a cliff and it was that exact kind of boulder that I'm so fond of, you know, it has granules in it, so it has very good traction and shapes. Lots of nice shapes to climb on. And looking down at the picnic that I had climbed away from and the people were tiny little people down there. I had climbed 200 feet, 300 feet. I think until I looked down, you know, and saw how small the people were, I didn't really have any sense of what fear or you know, that moment of looking down that makes your stomach change. But until that moment I was just fine. Just, you know. So in other words, I had sort of primal relationships to nature.

I don't know if I… Ecology, I guess ecology sounds like you're taking it up as a way of viewing the world through a kind of filter. You know, like astronomy might be another one, you know, where your…everything is filtered through what you see through a telescope and what you determine the stars are doing. And so ecology sort of sounds to me like you're filtering the world through thoughts of trees and forests and fields and animals and all of that. I'm not sure I had any such thought, so I'm not sure it qualifies as ecology when I was in New York, you know, anti-natural place as it is. But yeah, I can see in my life that what I was attracted to was the…outliers. And so, I was attracted toward Cunningham and the avant-garde arts. I was attracted to pursue an arts career from Arizona where there was no artists around yet. There were no artists in my life at all. I didn't know any artists, certainly didn't know any dancers except the ones that kind of enlisted me to be in their local companies, you know, eventually. So I got there by being a gymnast. So that gave me a pre-created flexibility from that kind of work. So then dance was a natural. And then…but what is it about gymnastics that has ecology in it? And I would argue that it's the body, and the mechanics of the body is how you're approaching ecology, is that we're of the body. Dance pursues that. And then art starts to turn it into something of spirit and imagination and mind. And then having the contrast with Aikido, having the contrast with yoga, seeing, you know, all these different premises, Tai-Chi. Having all these different premises to examine, you know, which was the fruits of living in New York where there was a lot of stuff, would not find that in a country. So that was quite…that was the ecology in New York, I guess, but it was human ecology. Agnes Martin, the painter who is famous for paintings of lines, you know, kind of grids, told Simone Forti that the only thing left of nature in New York was gravity and yeah, gravity! So, what was gravity? You know, what did, you know, dancers should have some thoughts about gravity, I would think, all that leaping around. What are you doing? What are you playing with? You know, if it's not your attraction to the earth and its attraction to you.

Enlarging / The marginal1:35:50

Tom Engels Of course when I mentioned ecology, you read my reading of ecology as thinking thoughts about nature or trees. But for me, there's, I think, another kind of ecology. What I would call an ecology of practices, or where…and we talked about this, physical practices that you exercise yourself, but by doing so, you can also enter into another relationship with the outside. So, I'm not necessarily thinking ecology as nature and its systems, but also our systems and how they interact with environments and to see those maybe as a whole.

Steve Paxton Yes. I think that's generally what ecology means. You know, like talking about a bird in its setting with the kinds of trees that it depends on with the, you know, kind of insects that exist there kind of thing. Right? Everything, it's interrelationships. The thing about being a dancer is that you, I guess those interrelationships are unnecessarily sort of scant, it doesn't matter about…many things don't matter. What does matter, you know, for the dancers, especially a beginning dancer is, what would you say? The ecology of the studios, the ecology of the classes, the ecology of the performances. I don't know if you could…I don't know if it's useful to use ecology so broadly as that, but I take what you said. And it has always been, there's always been an appetite for enlarging, but there's also been this appetite for the marginal, you know, the avant-garde arts. You know, I never ever thought of being a classical dancer or, you know, getting involved with being around, seeing classical arts. I've only seen classical arts, you know, because they're so available and you do see them, you know, and you find out a bit more about them. But I never studied them nor cared to particularly. I don't want to know about Renaissance painting. I don't want to know about the English landscape. I don't want to know, aside from…yeah, I can enjoy a painting. Had a hell of a time going to the Uffizi and…

Tom Engels In Florence.

Steve Paxton Yeah. Walking through and seeing the development of painting as they presented it, which went from religious icons, which were, you know, just really boring paintings, you know, little figures to keep your mind concentrated on the qualities of one of the saints and to in one afternoons'…traipse through the galleries and to Botticelli's Venus…

Tom Engels The Birth of Venus.

Steve Paxton Yeah, Birth of Venus. Which is just such a Hollywood production by comparison with these little brown icons. You know, two-dimensional, you know, figures, in very small and little brown frames. Yeah. The whole explosion of really florid painting and really watching subject matter go from this is a saint you must worship, you know, or want to worship…this is the one to keep you, keep your mind so you don't forget in your life that this saint is your saint or whatever. An aid. An aid to memory and spirituality, to other religious but still very connected people. And Jesus', you know, Mary's - people right around the central iconography of Christianity. And then starting to include paintings of pagan gods. So, yeah. And then starting…and the painting gets a little bit more florid and you know, I mean these are gods with quite a reputation for dash and splendor and all of that. So…and then somehow the whole thing opening up the space of religion to include paganism, to include primitivism to include…and occasionally there had to be ordinary humans in these paintings, you know, to receive the deity, you know, to adore the figure, you know, Christ on the… there are these soldiers and women and what have you around the foot of the cross. And so then they get to be the subject and then you start to get into what became… What, an ecology in the arts? Would you say? That got more and more inclusive of humanity? Because I don't know if there was…I don't know about paintings that I didn't see in that museum. You know, I don't know if there were portraits, I don't know if a portrait was a possibility, but I think a representation was more what was shown to me, not a portrait. Although we did get to Leonardo and it was an annunciation. And this annunciation was hilarious. I really cracked up because after the repression of probably 30 rooms of icons and two-dimensionality and expressions of dire seriousness or you know, sadness or adoration or whatever. Leonardo's annunciation is a very good-looking angel, but I don't think…I don't remember that he had wings. So, annunciation is prior to then, it was very clear you wanted to announce it, you know, or show. You want to demonstrate who the angel was, who the spirit of the Lord was, you know, little gold dotted lines going from that angel to Mary, which is the planting of the seed of Jesus, you know, in her womb and expression of some surprise on her face, you know, like trembling hands and you know, great moments, presumably. So Leonardo's…the angel is a guy in robes, kind of prepossessing, you know, very intense look on his face. Mary is sitting at a table, apparently having coffee in the morning. There's an open door behind her on one side in which you see a bed and the bed is made up very neatly. Now you know that that had to be a choice. Why is that bed there, you know, unmussed. Suggests not much activity.

Tom Engels Exactly. [laughing]

Steve Paxton Yeah. Or something. You know, there's…it's trying to suggest something, and Mary is reading a scroll, I assume it's the morning scroll of the news from the village, Bethlehem, you know, whatever. And you know, she wasn't in Bethlehem yet. She was wherever they were before Bethlehem. But anyway, reading a scroll and she looks up and there's this guy, and he's inseminating her or, announcing the fact that…

Tom Engels That she's pregnant.

Steve Paxton The pregnancy or something. And it's all just done with, yeah, I would say, a method acting style of painting. You know, where everybody's enacting their role in a moment. And you don't get the symbols, you don't get the little gold dotted thing that was happening in so many of the previous enunciations, but you get an intensity on the angel's face or the man's face. Mary is surprised, you know, as if she just looked up and saw him suddenly there. It just struck me as a…in eliminating all the symbolism, he had gone to a different kind of way to portray the moment of this miracle. And then you'd go around the corner and there's Birth of Venus, which is quite a large painting. Paintings are getting larger and larger. We went from galleries where the paintings were, how many centimeters by how many centimeters would you say…

[SP indicates the measurement of the painting with his hands]

Tom Engels I think that's 10 by 15.

Steve Paxton Yeah. Sort of. To the Leonardo which was like this, what is that, would you say?

[SP indicates yet another measurement]

Tom Engels That would be 70 maybe, 80.

Steve Paxton Just a minute…Leonardo was about…

[SP measures with a measuring tape]

Tom Engels It's 80.

Steve Paxton Yeah, well…It was at least 80.

Tom Engels [laughing] I am surprised by my estimation.

Steve Paxton Yeah, very good. By 50 let's say, something like that. So that's quite a bit bigger. And then the Birth of Venus is a real wall piece. It's huge by comparison. So, things were just getting more and more extravagant in painting. It's very instructive, I must say, you know, for an artist to recognize that there actually was a development, there was a trend. There was, you know, a reason why nobody did landscapes or portraits…and how portraiture sort of arrived, you know, and how spectacle arrived in paintings, as it turned from purely functional in terms of religious direction to speculative, fictional, colorful, dramatic, enormous…cheap!

Tom Engels Cheap?

Steve Paxton Can I say that…cheap? Can I say that in the sense that a stripper is a cheaper version of an actress? An actress is a more dignified and serious, artistic pose. A stripper is taking one aspect of that actress's possible range. You know, the seductress might come into an actress's role. And that's all it is. Yes, we're going to have a whole cheap art form of seduction, which is both hilarious and futile, you know, nobody is seduced by a stripper. There are aroused though, you know, it's arousal that is sought. And I felt like with the Botticelli, it was a little bit…the arousal factor was higher than a serious artist would have…

Tempering the mind1:50:48

Tom Engels Is that something, now you're talking about painting, but I have the feeling that it's exactly those unpredictable elements that you bring in, into those pieces that I mentioned that bring a sense of real life and real time. And so it's not ornamental in any way. It is what it is, right there, at that very moment.

Steve Paxton But what is? Say it again.

Tom Engels For example, like if you put the animals on stage, they are what they are. And so, then we…

Steve Paxton Yes, it's true.

Tom Engels There is like a sense of non-ornament, but there's also what I said before, the sense of openness or letting something be, or allowing something to be, etcetera. And I was reading a statement by...by Trisha Brown. I think I saw her hanging on the wall there.

Steve Paxton Yes. She's up there.

[Steve points at the portrait of Trisha Brown hanging above the kitchen table]

Tom Engels She was talking, still speaking in the line of opening and allowing, she was talking about improvisation as a way to temper the censoring behavior of the brain, or improvisation as a mode to allow uncensored decisions which affect movement. And I'm also interested in that notion of censoring, because censoring implies exclusion. It's in a way going against…

Steve Paxton It implies tempering. I mean you used the word tempering and I was a little shocked to think of improvisation as tempering and yet, yeah, willing to go for the ride, you know, but…

Tom Engels Yeah, there's a paradoxical…like to temper the censoring behavior.

Steve Paxton We are stuck in a situation as humans, that if we're functioning well, then we have a number of senses which inform us about the world and through which we get information, including from our family and from our school and all of that. The senses are trained, certainly by school, so that we use eyes a lot and ears a lot and movement is suppressed. And then separately and less…we spend less time playing with our bodies, you know, in sports or whatever, you know, equipment. Yeah. Environments. At some point we are informed that our senses don't include all the possible things there are to sense, you know, we don't sense certain light waves, we don't hear certain sounds, we don't taste or smell certain things etcetera. So that means that we are made aware that we have automatic limitations and that the culture in which we are developed has also certain limitations to do with…well what? Roughly it's architecture.

The culture has a structural element. So as a child entering the culture, leaving the family for the first time going to school usually is the route, if the culture is functioning. And that school is determined by what the culture thinks it wants people to become. And so you are trained to become a person who can sit in a chair for hours and hours and hours and hours every day, who is on time, who's, you know, amenable to the schedules, who can take information in their heads from other people, and from books and films and can at the time when they achieve physical maturity be given a passport, you know, a certificate to say that they have done the training and they are now of an age to do what? Well, all they have been trained to think of to do is work…home, family maybe later on, support themselves. I must say in America we have very, very bad transition from school to work, for some kids anyway.

Tom Engels In which sense? Is there a missing link?

Steve Paxton In the sense…yeah, there's no link. I mean, you would think that school would have the potential to train you for a job which you would get when you graduated and then, you would have as a kind of support. But in fact my schooling didn't do that.

Tom Engels You would say that in general school is actually way more about reproducing what you've been taught? So like the ways of thinking, viewing the world rather…

Steve Paxton Yes that's what you're rewarded for.

Tom Engels Rather than to actually…

Steve Paxton They don't know how to teach imagination.

Tom Engels Exactly. So to break up, to find the self-sufficiency…

Steve Paxton But they don't want people who are imaginative. A culture can't want to develop people who are going to rebel against its…I mean, it wants…

Tom Engels Its fundaments…

Steve Paxton …it wants some of them, it wants some of them, but it wants them very much under control. And it doesn't want too many of them. It wants people without imagination who do the jobs for their lives, you know, and under the best conditions, they then get put out to pasture and supported until they die, you know. But that's the best that life offers most people.

Tom Engels Did you ever…

Steve Paxton I was going to say that these restrictions exist for a reason. I was going to say that they're not mandated. It's not mandated that you get a job and start a family and raise kids and put them into school and start the whole cycle all over again, and gradually age out of life, you know, into some glorious old age home, you know, and in your village or town or something like that, you know, and die. That's not mandated. You have lots of choices. But, so the question is how can you suggest, or permit, or encourage even, people to see that the basic structure into which they've been initiated isn't all there is. So then these questions that we started with in yoga and Buddhism, in tai chi, in aikido, in the arts, become more interesting because, they're the keys to…even just by the contrast, even if they don't actually promote imagination, you know, they're the keys to leaving the structure as the structure has conformed itself.

Tom Engels You were just saying that of course there's people that are allowed to think differently, but they have to be controlled.

Steve Paxton Well to some degree.

Tom Engels To some degree.

Steve Paxton Like how did I live? I was not supported as an artist. I made some money performing. The performances weren't very usual. If I had taken a different route and gotten a job dancing in a Broadway show, I would have had a lot more financial remuneration for dancing. Or another kind of dance, you know. If I hadn't been such an avant-gardist, if I had been more into the classical, even the modern dance, I could have gotten a lot more money out of the art. So yeah, I was an example of somebody who could not be supported because my field had not yet been invented, because I was of the sort that was going to invent my own field. Even I, you know, liberal and socialistic creature that I am, don't think it's a really good idea to give somebody who's just farting around a lot of money. You know, like, I wouldn't think of giving the kids here on the farm a grant, you know, to do whatever they want, when they turned 16 and got their driver's license and could suddenly go off and get really into a lot of trouble because, you know. Or a young artist, you know, I think there's a reasonable expectation that they should suffer and struggle…and it just turned out for me that in coming here to the farm, my struggles suddenly turned extremely pleasant. In fact, my life improved a lot. Even as the struggling continued. And so obviously I had some idea that I didn't have to be in a structure. But it's again, about this appetite for marginality, you know, which I always had.

Tom Engels At the same time…

Steve Paxton I was always looking for the edges of things.

Tom Engels Yeah. And I think there's been a couple of moments where these edges, are very stark in the sense that you have dealt at some points with censorship, right? And that that is exactly the moment where the controlling instance says, “This is not possible. This cannot be thought. This cannot be seen."