3: Influences and memes

The New York art scene00:00

Steve Paxton Yeah, when I first came to New York, it was in the late 50s. So, by the time I had sort of established myself and had a job with the Cunningham company and all that, it was the early 60s, and the artists who were around and you still had the sort of the end of the abstract expressionists. You had the sort of middle period post abstract expressionists like Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg, the young guys who were challenging and at the same time substantiating painters like de Kooning and Kline, and anyway, you got Lichtenstein and then a very quick transition to these guys who became the pop artists. But it was all with a very solid intellectual basis.

Myriam Van Imschoot What did you say? Intelle…?

Steve Paxton Intellectual. Yeah, you’ve heard of the intellect? It’s sort of like the internet. [laughing] So in talking to them, I was very interested in who they were interested in. And I found out it was…for Rauschenberg, for instance, who I talked to a lot in his work at Judson and his work with the Cunningham company that we shared, you know, that space, it seemed to be…of course, Picasso was a major influence, because of his ego in a sense, because he dared to go through so many periods and be so brilliant in all of them. Ego, not in the sense of vanity although I’m sure that was part of it, but ego in the sense of he could find himself in many places and identify himself there.

Myriam Van Imschoot He could reinvent himself.

Steve Paxton Reinvent himself? Well, sort of the same thing as being able to find yourself in a space. Sometimes you can't find yourself in spaces that you enter, even in your own mind and in private, you can’t find…what am I doing here? Am I thinking these thoughts? But so there that was that. And then they were the obvious…I mean, Picasso partly because of the early collaging. I think that was a very big influence on Rauschenberg’s combines.

Robert Rauschenberg used the term “combine” to indicate a series of works that combined aspects of both sculpture and painting. Minutiae (1954) was one such combine, which also appeared as a set for the eponymous piece by Merce Cunningham. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot He called them “combines”?1

Steve Paxton He called paintings c-o-m-b-i-n-e-s. They combined sculpture and painting, so he called them combines. Because people said, “Is it sculpture, or is it…?” [coughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes. I mean, I know the word, but also in a different way…

Steve Paxton He just did it to short-circuit the argument about whether it was painting or sculpture that he was doing, and successfully. The critics swallowed it whole and started calling it that and the argument stopped, and they got on to other issues, which was always good.

Robert Rauschenberg, Minutiae, 1954, Combine: oil, paper, fabric, newspaper, wood, metal, and plastic with mirror on braided wire on wood structure, 84 1/2 x 81 x 30 1/2 inches (214.6 x 205.7 x 77.5 cm), Private collection, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

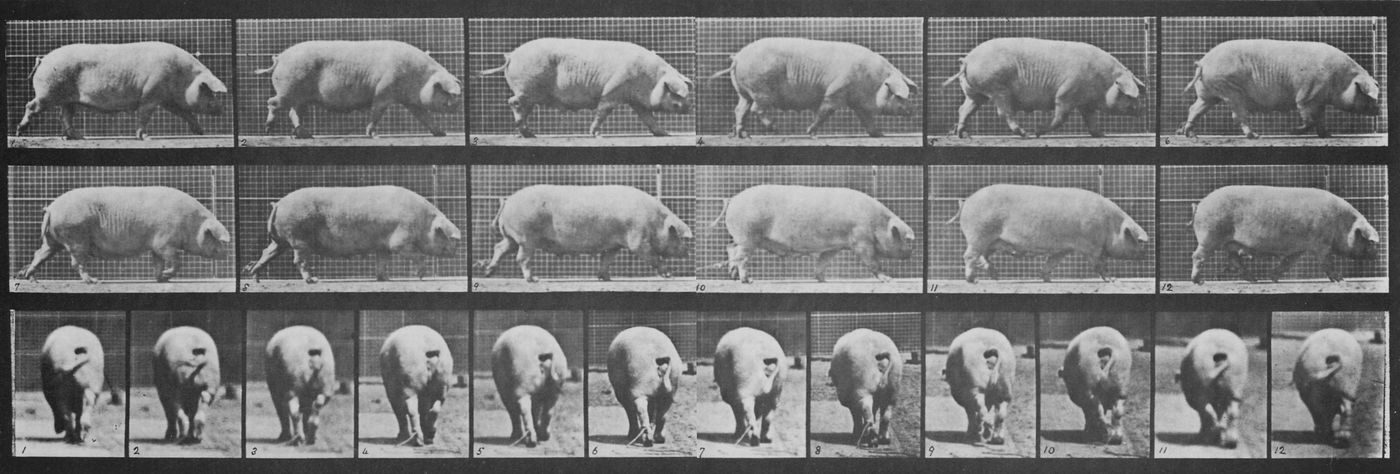

Picabia, another early collagist. They liked [Giorgio] de Chirico for the weird space… Uh, a young art patron that I knew was very interested in Muybridge, in the early photography, his photography experiments. And so, there I realized that there was really quite a lot of question about how even the simplest movements by any of us, in any of us animals, can be questioned and can be quite beautiful to examine, which I’m sure had a big effect on my pedestrian aesthetic — making walking dances kind of thing.

Magritte. Yeah, there was a bit of interest in the surrealists, but Magritte is such a confrontational surrealist. He poses his mysteries without anything extraordinary happening, you know. Like you are looking at the back of this man with the hat on, or you’re looking at the apple, or looking at an apple in front of a face, or, you know…he had a slightly different…and they liked that direction.

So, I looked at all those people, saw their shows, and I mean, of the ones that we have mentioned, and paid more attention perhaps than I would have to them…and I think just that thing of having one's attention directed is very much where…if you’re young and as uneducated as I was, has a very big effect on what you base your dreams on for your own work.

The other thing is that these influences were all either far away in time or space, but the ones right in my face - my peers and my superiors - were the kind of influence where you couldn't use their material. Like it seemed very clear to me that if these young painters weren't going to become young abstract expressionists… Actually there were second and third generation abstract expressionists as well, so that was quite a big field. But really, the primary abstract expressionists are just about all we remember. The primary pop artists are just about all we remember. We look for those at that level of origination. So you had to sort of originate something, didn't you?

Myriam Van Imschoot Here we go again.

Steve Paxton If you were going to be Cunningham, you know, and be making dances in that…Cunningham was very much one of my heroes, you couldn't do Cunningham. That's exactly what you couldn't do or else you were just secondhand Cunningham. So yes, after I left the company, I had to go through a big deprogramming event, which I think was a lot why I was so interested in making walking and other simple movement things.

Myriam Van Imschoot Did it feel less threatening to accept influence from peers that worked in a different discipline or in different medium? Like, for example, Rauschenberg’s…

Permissions07:07

Steve Paxton Rauschenberg used to talk about permissions. Artists open up permissions. So, this is a little bit different than influence because influence is sort of like, you know, you eat or you inject or you somehow it becomes a part of you and you carry its energy onwards, but permission is more like, well, Franz Kline works in black and white, you know, so therefore, yeah, graphics is a whole area of exploration. Rauschenberg works with, you know, perhaps two or three hundred images on a canvas. Therefore, multiplicity is a possibility. But at the same time, there's kind of the indication that Barnett Newman used to just do canvases that I later thought of as urban landscape. It would tend to have one stripe down the center, you know, and I suddenly realized, oh, maybe he's looking between buildings and the sky, you know. This is actually urban landscape that he’s reproducing here although they were much more mysterious than that. But you know, this urge to decode that we all have.

Myriam Van Imschoot But did you permit yourself to be more permitted by…

Steve Paxton …some people than others?

Myriam Van Imschoot No by visual artists than say like dance people because, you know, this whole…

Steve Paxton In terms of permissions, I think the permissions around the Judson — you know, Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, Simone Forti in particular — gave me permission to do my own thing. So, in other words, it’s not quite an influence. It's more like they made a very private and strong event come from their own speculations, their own thinking, their own sense of possibilities, and they're all different. So, therefore, I must be as different as they are from each other. That's the kind of thing a permission gives you, and I didn't think to be strongly different than they were from each other. I sort of fit in, you know, I was another aspect, another facet of the Judson situation. Maybe an important influence was Cage. But again, in this permission way because I discovered that he had made several hundred musical notations, made-up notations, to create music. Surely… [walks across the room to get a handkerchief] …surely, 99 percent of musicians just go along with the notations that they learn and make music by either observing or going against that form, but Cage wasn't even interested, particularly, in the typical musical forms. So, he and a number of other musicians as well were involved in making new notations. So you start from structure, in other words. So, that's a very big permission.

Muybridge11:00

But I really think Muybridge, especially for the early walking dances, was a very big influence. By that time, I had known about Muybridge just long enough to sort of forget about him, you know, to forget that I had learned him. And I think that that very often is the case that you get an influence, you absorb it, it goes into your subconscious, and then suddenly you have a bright idea, you know, five years later and come up with a work that if you were… Well, when you’re young, you don't know how the subconscious might work, but that definitely, as I look back on it, I say Oh, my goodness, I started my work being very interested in performing Muybridge, as it were. Not a very big jump.

Myriam Van Imschoot Sorry. What did you say?

Satisfyin Lover (1967) is a choreography by Steve Paxton in which 42 people cross the stage from stage left to stage right. ↩

Steve Paxton It's a big jump. It was a big jump from Graham. It was a big jump from Cunningham, but it’s not a very big jump from Muybridge to Satisfyin Lover.2 In fact, no jump at all. [laughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot [with irony] Well, it's a small step for you but a big one for humanity.

Steve Paxton It's the same old size step for all of us walking.

Myriam Van Imschoot Muybridge. Would you have seen that in books? Was it available in books?

Steve Paxton I saw… Yes, it was definitely available in books. It went sort of out of print. And also this young…this young guy had found prints in some old bookstore and bought them and was giving them to artists. You know, Look at this stuff, isn’t it fabulous? I got the pigs from the animal book - a bunch of pigs, moving.

Myriam Van Imschoot But they are amazing, I mean, those pictures.

Steve Paxton Why are they amazing?

Myriam Van Imschoot To me, they are amazing when I think about the fact that he showed for the first time things that had never been seen.

Eadweard Muybridge, Walking Pig (0,67 seconds), 1887, Wikimedia Commons.

Steve Paxton Well, by the 60s, we had film.

Myriam Van Imschoot By the 60s, you had film. By the 60s, there was a whole idea of, you know, montage, snapshot photography.

Steve Paxton The information that you get from stills is somehow quite strong to see. Oh, yeah, I can see the body changing from this to that to that and that's what happens. That's the mechanics that you see in this. You saw the mechanics in a very easy to absorb way, whereas in film, you have to just look at it as movement, and it just goes by, and you don't really analyze it. You can’t analyze it as easily - looks too much like the real thing, which you don’t analyze at all. It just happens.

Myriam Van Imschoot For the first time, I actually realized that in the 90s, when people would also more and more use walking and just very ordinary movement more than ever - I mean more than in the 80s, for example - is that the big difference now is that they don't integrate the walking because of the interest in the movement potential of the walking. It’s a very small thing, but actually, I realized that it’s a huge difference. Integrating walking as a sign of the ordinary or whatever or something that can be done, but without an interest in the mechanics of it or in the movement potential or anything.

Steve Paxton Or the expression of it. What it expresses.

Myriam Van Imschoot That helped me a lot in seeing what…

Steve Paxton But in Muybridge’s, I mean, he's an experimental photographer from the late 1800s. I think that’s his period. These photographs viewed by an artist 60 years later, I think I aestheticized what for him might have just been photographic research - nothing to do with aesthetics beyond photographic potential.

Myriam Van Imschoot You aestheticized?

Steve Paxton And I was involved, I had already been involved in that. I had…I had a private influence as it were, prior to that, which made his work really accessible to me, which was, as a dancer, I was training my body as much as eight hours a day to do unusual movement and to do it in unusual ways. Like to remember every movement and to be extremely precise and do the same movement again and again and again, yeah, to be a dancer in that sense. I was very curious about the relationship of my body to its normal movement when I wasn't training. I was very curious about what was happening the rest of the time when I wasn't willing it to do things and it was just doing things. So, in a way, looking at Muybridge was to find a way to pursue that fascination outside myself into another artist’s work.

Lucinda Child's Street Dance17:06

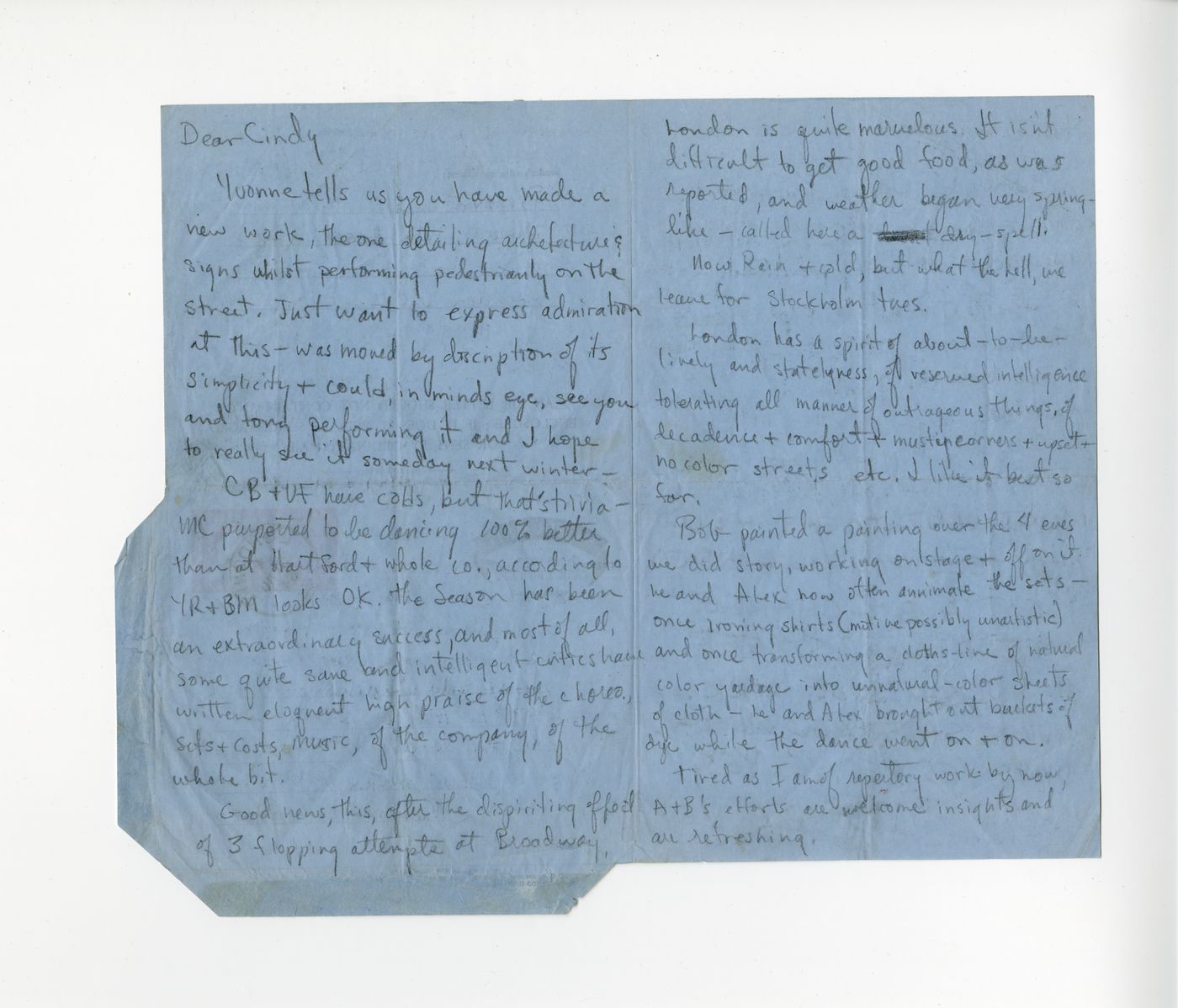

And this happened many times, I have to say, Lucinda Childs did perhaps the best pedestrian dance I ever saw - a dance that happened in the street. I think I told you about this.

The choreography by Lucinda Childs, here referred to as City Dance, is actually called Street Dance (1964). Street Dance was the result of an exercise Robert Dunn gave his workshop participants, i.e. to make a dance that lasts six minutes. The audience looked down from an apartment onto the streets where the performers, who blended with the passers-by, would draw attention to certain architectural features of the surrounding buildings. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot The City Dance?4

Letter written to Lucinda Childs by Steve Paxton from London while being on tour with the Merce Cunningham Company, 1964, Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse - Fonds Lucinda Childs, Courtesy of Lucinda Childs.

Steve Paxton Yeah, City Dance.

Myriam Van Imschoot Looking out of a window and seeing…

Steve Paxton …yeah, the audience… [blows his nose]

Myriam Van Imschoot You have a cold.

White Oak Dance Project was a dance company founded in 1990 by Mikhail Baryshnikov and Mark Morris. In 2000, White Oak Dance Project revived both Paxton’s Satisfyin Lover (1967) and Flat (1964). ↩

Steve Paxton Yeah, I woke up yesterday with it. It seems to be lightening up, I hope it will go fast. But in her work, you know, when I saw her work, I realized where I had gone wrong in my aesthetic of trying to study the normal movement, which I had been involved in by the time I saw her dance [for] probably five or six years, I had been asking myself this question. It was very much the way I had predicated my own work, you know, normal movement, you know, what is it like to compose with this as opposed to special movement with high pacing and lots of variations in energy and all that business. And uh… I saw her work which was out on the street and in which you accepted the passers-by as part of the set or the other performers or something - I don’t know what - of the two dancers who were on the street as well, doing normal movement things. And I realized where I had gone wrong was to put my work in the theater at all. Gone wrong and at the same time, gone right in a funny way. I wasn't getting to what I thought was there because everybody who performed in Satisfyin Lover in the theater was self-conscious - very hard to get unself-conscious walking, especially when the idea was new. And people were saying, Walk normally? How can I do that when I'm walking across the stage and I'm being seen by hundreds of people? But, nowadays, when White Oak3 did it, I thought people did it rather well, and they totally got the idea. So, it seems like…it seems like the public, the general public now have no problem understanding this idea and get it and perform it well. So, in a way, my work has gotten better over the years. I used to fight with certain people about the way they walked.

Myriam Van Imschoot How would you try to redirect them towards normal walking?

Steve Paxton Well, I just didn’t have any tool. How do you? Once you say, “Be self-conscious,” how do you change that mentality? It’s very hard. […] I chose a paradoxical situation.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. And that's what made it. But is that or would there be other reasons why you would have said, Well, City Dance shows me possibilities I haven't taken into account while studying?

Steve Paxton Yeah, but I couldn't do it because she had done it. You see, so I was actually blocked from what I wanted to get to by her rules. It was like an aesthetic snooker game. She snookered me from my desire. Not consciously. It wasn't like playing a game or having a relationship on that level. But in fact, that's what happened, I recognized later. But I didn't mind because I had done my work - all the walking and standing and sitting stuff. And you have people tying their shoes and other fascinations I have for normal things. And I figured well, whatever it is that I have made even if it isn't this thing that I had seen somebody else do that seems so much more perfect in terms of re-presenting and illuminating normalcy. Still, there are interesting things to observe. And it's interesting, the whole psychology of the paradox that I’m working with. It's still something, it isn’t like it was nothing. I didn’t discredit it or discard it or anything like that. I accepted that I had made it but that I hadn’t been clever enough to figure out how to make it… But she may not have even been interested in that aspect of it, because she…I’m not sure she's… First of all, she has always been a mysterious artist, so what her influences and sources and desires are, I’m not sure. I just know she made really good work.

The pedestrian24:52

Myriam Van Imschoot How much was the desire to erase the borderlines between art and life? How much was that part of the enterprise when you started focusing on ordinary movement? Was it part of that?

Steve Paxton I wasn't really aware that there was such a distinction nor a distinction, you know, the Cartesian distinction between mind and body. I wasn't aware of those thoughts, you know, these principles. It was just clear to me that, I mean, I would explain it a whole different way now: I was interested in the subconscious. I am interested and still am interested and have, you know, kind of a big theory in my mind, about what the subconscious does and why we think that we only use 10 percent of our brain, you know, what the other 90 percent of the brain is doing, if you really use 10 percent of it. I think we might use 10 percent of it for consciousness. And the rest I think has everything to do with where we are in space and time, just noticing all the differences that are constantly happening around us and adapting ourselves to them. It’s a kind of hidden reflex with everything. So it isn’t like the kind of reflex of an eyeball, you know, because you know clearly where the ball is in the air and you can somehow get your hand and your eye to coordinate the catching of that ball. But imagine that you’re doing that with the weather and the birds and the people and the buildings and the objects, each movable object, your sense of its permanence or transitory nature in the place where you see it. And now, since I'm thinking about space, I see a kind of limitless space as a necessary subset for being able to see what is in the space. In other words, when we think about space, we usually think about the edges of the space, you know, the walls of the room. You say the space in the room, and everybody understands the ceilings, the floor, and the walls make that space happen. Also the objects in the room, so the interior decorator comes in and makes the space seem very fluid, and the colors are all gorgeously interconnected and, you know, makes a kind of painting in the space or a painting, and it's illusory spaces and it’s, however the painter plays with space. Yeah, so the idea that there might be an incredibly fast, very, very complex, giant part of the brain operating, and that the consciousness is actually much slower and much more connected to events like language or events like sharing. Say that you go for a walk with somebody, you say, “Oh, look at that tree.” “Oh, yes, that’s a lovely tree.” That kind of thing that you do, language and…all of which happens at a much, much slower level than reflexual understanding about a space means that the processing done by the subconscious is incredibly faster and that the part of the brain that we are self-aware of is a rather slow and a limited kind of part of the brain.

Myriam Van Imschoot I only realized way too late your huge interest in psychoanalysis, as well.

Steve Paxton Do I have one?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton What do I have?

The Schreber Case29:07

Myriam Van Imschoot You've been reading [about] The Schreber [Case].

Steve Paxton Oh yes. Oh yes. That was interesting.

Myriam Van Imschoot When did that come up?

The name of the Russian count is Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin. ↩

Steve Paxton Well, I was at Dartington, doing a bit of research. I was researching two things. One is the Darwinian theory and the way it's been interpreted by the public and so, essentially social Darwinism I was interested in. Poor old Darwin, he's been, you know, like Freud and Einstein, we use him for…to excuse our behavior in many ways. Yeah, but Darwinianism and its connection to capitalism kind of thing, you know, 'nature red of tooth and claw,' it's important to have death and birth going on all the time… And then I found this Russian count5 — what was his name? His name escapes me now — who contrary to Darwin was saying that species…and this would be an aspect of Darwinism, I suppose, really, not contrary to Darwin, but contrary to social Darwinism and all of that ‘It's a jungle out there kind of thinking,' was discovering ways that animals cooperated, and even sacrifice themselves. So, on the one hand, there's…I think the overriding theory is that each animal is interested in getting its own genetic material passed on to the next generation, and he was pointing out that there are animals in herds, for instance, one animal will sacrifice for the rest, or, you know, or like the mother bird that pretends to be injured and puts itself on the ground in front of the cat to lure the cat away from the nest kind of thing. All kinds of examples of cooperation and inter…within one species, caring about each other, so at least the species continues. And then you start reading about the interconnections between certain animals like this insect lives for a certain time in a certain kind of rainforest orchid and then it moves into the gut of a passing caterpillar, you know, and then it is…you know, that caterpillar is eaten by a certain bird who, you know, when the bird has shit it out again then it makes the next mature form of itself and it can breed or whatever. This kind of thing, so the whole thing of symbiotic relationships. So one starts to see that even interspecies, there's all kinds of stuff going on, and then you read about our own mitochondria in our own cells is something that actually was once a separate animal that is now…

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s clustered into another organism.

Steve Paxton Yeah. So and we have all kinds of fauna in our stomachs that we need in order to be healthy.

Myriam Van Imschoot Flora.

Steve Paxton Yeah. So that it’s uh… So that was one aspect of the research. And then I got very interested in paranoia. Because this is another thing, like social Darwinism, which has, we use all the time. We need this idea. Oh, you're just paranoid, you say. I started thinking about paranoia, and I realized, Oh, yeah, that's…first of all, it's an act of imagination. So that's interesting because I'm interested in what imagination is for, you know, beyond making very boring dances the way I do, you know, like, what else is it for? How does it function? How do we learn what it is, you know? And I realized that that sense of unease, that sense of being in danger in a forest or a jungle or, you know, in an open, primitive life would be absolutely important. You get this strange feeling, you haven't actually seen or smelled or heard anything, you get this feeling like a leopard is at your back or the water buffalo is in that thicket holding very still, you know. These things would save your life if you were accurate, if it turned out that you were even 80 percent accurate in the sensation. So, I thought paranoia is actually something… The kind of paranoia we have, where it's an attribute where you suddenly feel like all your neighbors are down on you or your landlord wants to kill you or your…

The kind of mental illness paranoia has a lighter side, that it’s intuition. And if it's, if it's in a situation in which you’re involved, it would probably be an intuition which would save your life: Don't step on that limb because it's going to break, you know, with that kind of thing. Whereas here, it's Don't be around that person because there's some kind of danger, but it might be that you have a sense of danger for vast reasons that are not to do with your individual safety but with things like the bomb, with things like the Cold War, you know, these stresses that we live under for years and years and years that might make people re-identify the danger in their immediate surroundings as opposed to recognizing that it’s just something…it’s a pressure that’s on the whole nation, for instance. So I was very interested in paranoia and also to do with…because it, in our species, would be in some ways a Darwinian determinant. Anyway, it's a very important mental illness or aspect of mental illness and gets used all the time. And I was also trying to figure out was I paranoid? I thought, No, I am not in the least paranoid. That's what I thought at the moment. And then I started thinking about it over a couple of years, and I thought, yeah, I probably did have some paranoias, you know, some little… I noticed I didn't have any phobias, and suddenly, I discovered that I had a shark phobia. When I was visiting an island in the Caribbean, I suddenly discovered that sharks could make me panic in the water and so that was…I finally found a phobia. So I thought I didn't have paranoia the same way I discovered I did have little aspects of paranoia that I was…where I sensed danger.

The piece directed by Paxton was called 1894 and was performed in 1984 at Dartington College. Some years later, in 1986, Paxton and Kilcoyne founded Touchdown Dance, an initiative to teach Contact Improvisation to people with a visual impairment. ↩

Sigmund Freud, The Schreber Case, 1911. ↩

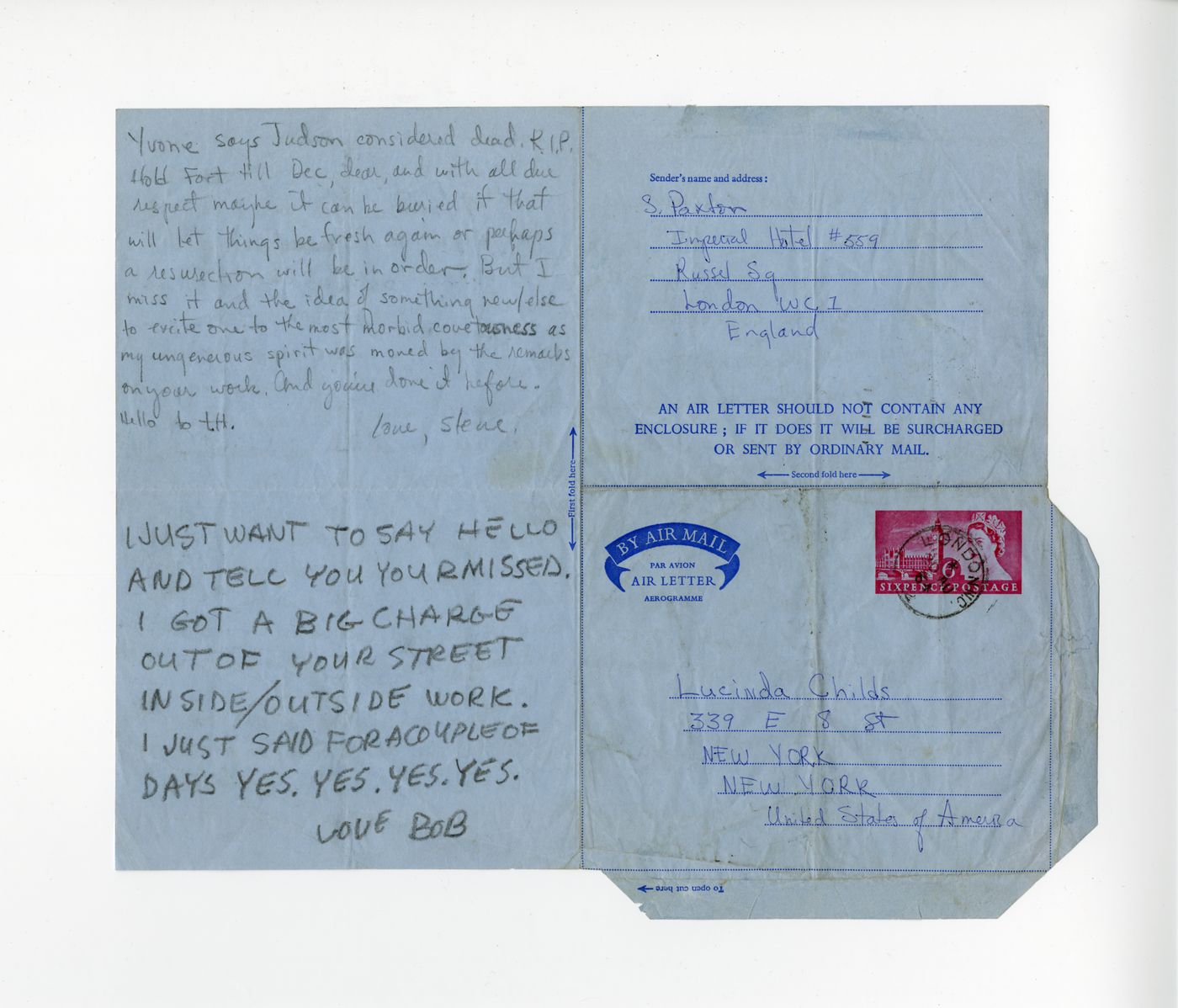

So Schreber17 is the case in which Freud…which Freud used to demonstrate paranoia, his theory of paranoia. So that was a lot of fun. And then what was even more fun was I was doing this research with Anne Kilcoyne6, who was in the drama department at Dartington where I was teaching. She's a psychologist, so she knew where all the history was. We started with a book that Schreber himself wrote, which is all that Freud ever knew about Schreber, so it's a very interesting case because you see the psychoanalyst at work, and you see exactly the material that he was using to make the theory from. And Schreber's book is an amazing book filled with, obviously, images by somebody who was mentally ill. But at the same time, why do these images exist? And one of the things that seems to be pointed to is that his love, respect, and religious training that his father gave him got shifted after the father's death to a higher authority, which was probably the government, the German government. And then after he became mentally ill got shifted to a kind of twisted idea about God and what God was doing - how God operated. So, you could see this need for an authority figure being part of his… And I think the way Freud was interpreted, I don't know, I haven’t read all the material, was that Schreber, who was a crossdresser, seemed to want to dress up in women's clothes, although I didn't see any evidence that he was homosexual, but Freud would assume that there was a homosexual attachment to his father and that as a result of the trauma of being in that position relative to something that was so taboo creates the mental illness. That you are projected into an abnormal state, or actually, they don't know what happens, but this is sort of the way it’s interpreted: You fall in love with your father, you, of course, don't get it reciprocated, you don't get to actually act on it, and it just… You get off the normal path, and in fact, you’re pathless because you've got this as a basis in your childhood.

Leonard Shengold, Soul Murder: The Effects of Childhood Abuse and Deprivation, Ballantine Books, 1989. ↩

Anyway, so we looked at all the research, and the research just went on and on up until the late 60s, when there was a book called Soul Murder18, written by a British psychiatrist who made all this terribly dramatic, you know, Schreber and his father. His father worked with kids and had a big gymnasium and a place for children to live, and he worked with children who were physically damaged with spinal bifida or just very, very bad posture and all of that business, and he made a lot of mechanical improvements for them, like a device that you put on the desk that holds the head up very high, so children don’t slump. He’s very against slumping. He liked the spine very, very straight. Sounds very German, doesn’t it?

Moritz Schreber, Ein Kinnband zur Vermeidung eines Fehlbisses, 1858, Wikimedia Commons.

But in many ways, it is. He didn't believe that children should carry their schoolbooks on one arm or play musical instruments that inclined them to develop different skills in one hand and the other. Another is he wanted symmetry and saw that a lot of activities work against symmetry. But mainly, he was working with bodies that were young minds that were very badly damaged in some way and trying to get them straighter. But when he illustrated his devices, he used his own children as the models, so you can recognize the two young Schreber boys in these devices, and it was thought that he had put…raised them in these devices, you know, the mad scientist experimenting on his own children, and so therefore, his… Well, to cut to the chase, his Germanic and fascist mind had caused poor Schreber’s illness, was sort of the popularization that the child is damaged by the parents.

But in doing that research, we finally found a young…I don’t know what he is, psychologist, I guess, in Amsterdam, who had written a thesis, his PhD thesis, and I laughed all the way through this thesis. This guy has no sense of humor, so it was all the funnier, you know. But he was very, very clear in that Dutch way of being very clear and just not giving a damn, you know: This is the way I see it, and this is the way I’m going to say it. So he said, Normally, the doctoral thesis is about research, and I’m not doing that. I'm doing for my doctoral research work which normally is done in the master’s research, and this is why I’m doing it. He said, This case, the Schreber case, has gone 80 years under certain assumptions and the reason it's gone under those assumptions is because every time the psychologist gets to the point of writing their doctoral dissertation on the case, they can't write about the nature of the history, they have to make some progress in the case, you know, or develop some new aspect. As a result, nobody has really looked at the history. Nobody has really looked at the facts. Nobody has gone back. And he was able to go back to wherever it was, to Dresden or wherever Schreber was, wherever he grew up - I can’t remember now - and meet some of the family, and visit the buildings, and hear the family histories, and see photographs. Nobody had ever done this. I mean, Freud had just taken Schreber's book and everybody else had taken Freud's writing and built 80 years of the theory of paranoia. This one young guy erased… The whole thing is a big, 80 year long piece of shit. It's incredible. And I just laughed my way through it. I mean, it was…he was so wry. He was so direct. And I had just spent all this time reading this material and all these pompous, self-fulfilling academics. And they haven't done their basic research. So that was the fun with that. And we went on to do two productions, one directed by me because we couldn't agree to direct together, and one directed by Anne. So, she supported me in the first one, but, I mean, we came to the point where we couldn't agree. What we couldn't agree on is how guilty the father was. She wanted to… The book that I told you about, Soul Murder, she wanted to produce that, use that basically as the script and dramatize it. And I said, Well, how can we do this to a presumably innocent man? We are condemning the father based on…

Myriam Van Imschoot …the book.

Steve Paxton Yeah, on erroneous theory. What's the point of that? This father was innocent. Turned out the father in this gymnasium had been hit on the head with a ladder at some point when Schreber was quite young, so actually he had been having migraine headaches up in his bedroom most of the time that Schreber was growing up. Then he had a few good years before he died, and then he died when Schreber was in his early twenties. And if there was a sexual situation, it turns out that probably he was molested by his brother and his mother found out. And because the father was so ill, they elected not to come clean about the story, so it was all suppressed. So Schreber had to live with what was, in a very religiously based household, a horrible crime against him. He had to live with, well, being a victim. So, there's a lot of reasons just in that one scenario for his later disturbances although one doesn’t know whether it’s…

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s nice to have two productions though. Two announcements and two versions and two…

Steve Paxton Yes. And this whole thing of being put even in these devices for his whole life? No, he was probably just…or at least one theory is that he was just the model for the artist who illustrated several of Schreber's pamphlets. Why would he have been in these devices? Because his body seemed to be in good shape. The devices were really for other children. So, all of that. In other words, the whole theory, here's… It's just the worst of academia, you know, and it turned out to be institutionalized badness. It turned out to be bad because of the nature of the steps that you have to take towards your degree.

Myriam Van Imschoot It kept you going for a while. [laughing]

Steve Paxton Well, yeah, I was interested in the process. I was interested in writing a play. I was interested in… I was interested in making a true play, a dramatization of something that had happened that affected us all, you know, the theory of paranoia. But, I mean, Dartington was not that intellectual a place, so the thesis wasn't regarded as very interesting, the fact that it was a theory of paranoia…explained… They were much more into drama and imagery and very not interested in a logical or intellectual line through a situation that wouldn't have… But because of my previous work in New York, you know, where I saw musicians working the logic through, you know, the new, the new structure that they've invented and the way, the people they choose to have play it and then the kind of instruments that they might select, and all that, just the kind of sense of invention at a structural level. Yeah, I was quite prepared to take on any pieces as… I mean, I've done, I've done a work on… My friend, Danny [Lepkoff], has done a work on infinity, mathematical concepts — a dance on infinity. And he and I together worked on - what do you call it? - quantum theory. We did a dance on quantum theory, a drama, a dance drama with lines and everything. So, I mean, anything becomes material at a certain point. And if I, if I’d had another brain, another kind of education, I might have been able to work and find my… Maybe one of the big influences I didn't have was a strict confinement inside a dance aesthetic. I didn't have enough of any one technique or any one repertory to kind of…or young enough to kind of firm me up in some clear direction with clear boundaries.

Myriam Van Imschoot You didn’t have a device or father in order…

Steve Paxton That's right. Yeah. I wasn’t confined.

Myriam Van Imschoot …for you to become symmetrical.

Steve Paxton Yeah, symmetrical and perfect, with ideas from outside, the aesthetic forms that I should have been following.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s quite a leap. That’s a leap. That’s a jump.

Steve Paxton It’s a circle, a little circle that we just made.

The study of perception49:29

Myriam Van Imschoot Because an assumption, just correct me, if it’s a wrong one. Starting to talk about consciousness earlier on in the conversation, it seemed that the interest for the subconscious is, in fact, not too far removed from interest in perception, even in a very empirical way.

Steve Paxton Well, the dancer’s material was, in fact, the body, and although all of this stuff is terribly speculative, and I don't trust almost anything as being solidly based that we read or find out about the mind and the brain. You know, current research is always changing. […] In a very practical way, you do have to look at these things.

Myriam Van Imschoot If you mention the subconscious, very often people will think of it in a, you know, Graham way: archetypes and…

Steve Paxton We get a lot of it.

Myriam Van Imschoot …and so on.

Steve Paxton The way rather bad drama is presented, the subconscious is the place of madness, is the dark side, is all of that stuff.

Myriam Van Imschoot It's interesting that originally, when you start being interested in it, it's much more empirical.

Steve Paxton Well, it's evidently there. It’s evidently doing quite a lot because my consciousness is not doing it.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. And it, of course, it deals with - how do you say it? - normalcy?

The standing still is often referred to as the Small Dance. It first appeared as the last five minutes of Magnesium (1972), in which the performers, after a very intense dance, stand still. For a description of the small dance, have a look at the interview Practices of Inclusion (2019). ↩

Steve Paxton Yes. Not really “normalcy.” I don't know if that word really has much - what do you call it? - currency. But what do I normally do? Or what do most of [us]…are there things that most of us normally do? So as in Contact Improvisation, one of the early exercises is the standing still.7 You know, what is that about? Why did I make that choice? It has something to do with each person examining their own structure and learning to have sensations, learning to look inside, which is actually something that, aside from dancers or various kinds of sports people, probably isn't done that much. We're not led to think that looking - utilizing our own body as a kind of research — is a possible thing to do. Indeed, I’ve heard it suggested that it’s a dangerous thing to do.

Myriam Van Imschoot So there, the subconscious is very much part of an investigation of perception, while in the later examples with the Schreber case and so on, it really goes more in it’s…it goes more to normalcy, you know, and the pathological side.

Steve Paxton Well, if we can't define normalcy, how can we define “pathology?”

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes, yeah.

Steve Paxton Especially about the last 10 years of…through various friends, really, I had a lot of exposure to mental illness and to the drugs that are used to control mental illness and I see that it's a horrible situation. I also have seen that we make it worse through misunderstanding it, through the kind of generalities, whatever dramas we think are involved with mental illness. The fear, the irrational, the paranoia! we have of mental illness. Okay. So [laughing] I think you discover that actually it’s quite copable with. It's copable especially for the person who's having it. A depression right now, a horrible thing to experience, but if it's dealt with lightly and very considerately, it can be ameliorated, it can be made easier, it can be made not so horrible, if they're not ostracized, if they're not feared, if they're not having to cope with their whole social world and their family structure deteriorating because they're ill as though the victim gets the blame. I've definitely seen that happen, and it's so scary to me that we have so little understanding of what's going on in somebody's organ, when your brain goes wrong, that we make them the victim of their own illness, and they get ostracized, and they can't help themselves, and people are afraid of them, and of course, under those circumstances, they would be desperate, you know, as they sense everybody withdrawing from them. It's horrible. It's a horrible social encounter. So, yeah, I'm very interested in these things, but I don't have any answers. I just kind of add them into the overall big bag of questions that I keep in my mind. And one of the things is, what is this subconscious, you know, what is…because one of the things about… Well, what is consciousness, as well? Watching my parents die and really being with them as it happened, and especially my father, the first person that I had that experience with, watching the degrees of consciousness that were present and the way they went away until finally, the sensing stopped, until finally the biomechanics stopped, and then death. It was actually a quite long process. And, well, drug experimentation on my own part plus…plus, you know, which puts you into different states, to realize that there are different states available. Meditation research, my own dance research, all these different states that one works in as an artist creates, provokes, in order to work.

Myriam Van Imschoot Do you think artists have more privileged access to those different states?

Steve Paxton I think artists are people who manage to cope with their problems in an expressionistic way. I think they have a privilege to making a living or making a reputation on their perceptions and that these perceptions are very often a little bit pathological. And I think that especially for young artists. That's why you get things…like work which is so dire, and why each new generation seems to grow up and find music that’s uglier than the previous generation's ugly music, you know?

Art families 56:39

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, if I would try to apply it, I don't know, but… I don't know whether it was Mary Fulkerson who said this, but talking about the contact improvisation, that she seemed to suggest that you went into that area because contact was so frightening.

Steve Paxton Well, that's one theory. I don’t think it’s that.

Myriam Van Imschoot Maybe it’s not…but to me it makes sense. Even if it would be on an individual…

Steve Paxton We play with psychology, you know, and say these things, and they all make sense in a funny way.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton What if I had a great talent…

Myriam Van Imschoot …for contact?

Steve Paxton …for contact?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton What if what I think I was doing was looking for my family. I had a very estranged…I mean, we were a loving family, but we weren’t physically close or anything like that. I kind of look back at my life and how many groups I’ve worked with, how many little art families I’ve been a part of and loved it. I’m so interested in all these things. So interested in the way art families, as it were you know, a little group of young people in Antwerp, you know, what they make. Why, you know…how they click together, how long it lasts. I feel really comfortable in those scenarios. The counterculture in the 60s in America, [I felt] very comfortable as I’m sure many other young people did. Definitely, it is a kind of tribe that I was seeking. Maybe I was looking for my tribe. That’s probably what it was. Not so much family, because my family was okay. I’ve heard of marvelous families where the parents are moral, morally upstanding and a great example for the rest of the child's life, and they have plenty of security and lots of kids to play with in the family, and they were all given training in music and sports and…

Myriam Van Imschoot You’re talking about your…

Steve Paxton No. Actually, I'm talking about Katharine Hepburn, whose biography I saw the other day on a film. It sounded like she had a very secure upbringing and she turned out exactly the way her family would have wanted her to except maybe they would have preferred she was not an actress. But she was clever and she was independent and she did a lot of good for women's rights, and her mother was a woman who was out marching, you know, at the beginning of the century, for women's rights and for the right to vote and all of that kind of thing. Her father was, oh, was he a doctor or something? Oh, he was, yeah. They both believed in the right to have an abortion if you wanted it, you know, to not raise unwanted children. Where’s the sense in that? So, that was… She became the movie star who exemplified, maybe not explicitly, but seemed to be the kind of person who would hold that point of view.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, they would call it that she didn't only have the genes come across but also the memes because the memes are the equivalent to genes.

Steve Paxton Maybe the cultural…

Myriam Van Imschoot …more cultural ideas or…and I love this whole idea of memes. I’m very fond of memes because it makes you very humble towards your own ideas in that you are not the inventor of an idea, but you are [a] vehicle…

Steve Paxton Definitely.

Myriam Van Imschoot …for ideas that use, well, use you as a vehicle to get passed on.

Steve Paxton It's weird, isn't it?

Myriam Van Imschoot And it’s so nice.

Steve Paxton …to think of being a vehicle for an idea.

Myriam Van Imschoot For an idea.

Steve Paxton “I am the author in this idea.” Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton Yeah, definitely.

Myriam Van Imschoot And Helena Katz, who you know was very interested in Darwinism and new Darwinism, she’s very much a part of this new Darwinian school, and she talks about dances through…from a meme perspective, much more than from a perspective of…

Steve Paxton One thing I saw in my touring and my investigation into little art families all over the United States was how often the same idea would be appearing in Seattle as Alabama, you know, as Salt Lake City as New York. New York got all the publicity because it had the apparatus, but the same ideas were occurring elsewhere. Sometimes ahead of the New York ideas. This happens in science all the time. It’s no longer… So that seems to me like ideas can bubble up, and some people are there to be vehicles for them, and so, yeah, if you have an idea that you think would make a good work, and you don't act on it but say, you write it down and you date it, put it in an envelope, that within a year or two, you're going to see that idea in somebody else's work. That's what I think. Maybe that's another reason that I…I sort of knew that from hanging around the artists. I could hear all this talk of influence and, you know, they would discuss these things, and they would say things like, Well, wasn't it Picasso who said, Yes, I take things from other people’s work, and I transform them, or I improve them.

Myriam Van Imschoot I make them mine, or…

Steve Paxton I make them mine. Whatever. Yeah. I do it my way. So who's to say whether you got the idea or whether you thought the idea?

Myriam Van Imschoot Or the idea got you.

Steve Paxton Definitely, the idea got you.

Marcel Duchamp1:02:26

Myriam Van Imschoot Talking about that, we are expanding a little bit the Muybridge model, if you can call it that way. What about the Duchamp, the second name you mentioned at the beginning?

Steve Paxton Well, I…

Myriam Van Imschoot Is it part of that meme lineage?

Steve Paxton Definitely. First of all, the ready-made, and walking as a movement ready-made. So very clear influence there even if Muybridge preceded him, you know. The nature of the objects. I remember seeing this work, I can't remember the name of it, but it's a birdcage with sugar cubes in it, only they are little marbles, but they look like sugar cubes. Yeah, that slightly surrealistic aspect. [sneeze] Excuse me.

Myriam Van Imschoot Bless you. Why don’t dancers ever sneeze on stage?

Steve Paxton I don't know. I've never farted or sneezed. I have coughed. [blows his nose]

Myriam Van Imschoot I have never seen someone sneeze on stage in my life.

Steve Paxton Yeah, a real…yeah, it's impressive. I think it’s hard to sneeze when you’re filled with adrenaline. I think it’s an organic anti…

Myriam Van Imschoot Anti-sneezing?

Steve Paxton What do you call it? What do you take for allergies? Anti…you don’t know this word. You do if I said it.

Myriam Van Imschoot There’s a lot of allergy in my family, so…

Steve Paxton Anyway, I think adrenaline is a pretty good one or some other hormone that's… Hormones is what we take for these things often. Cortisone is often given.

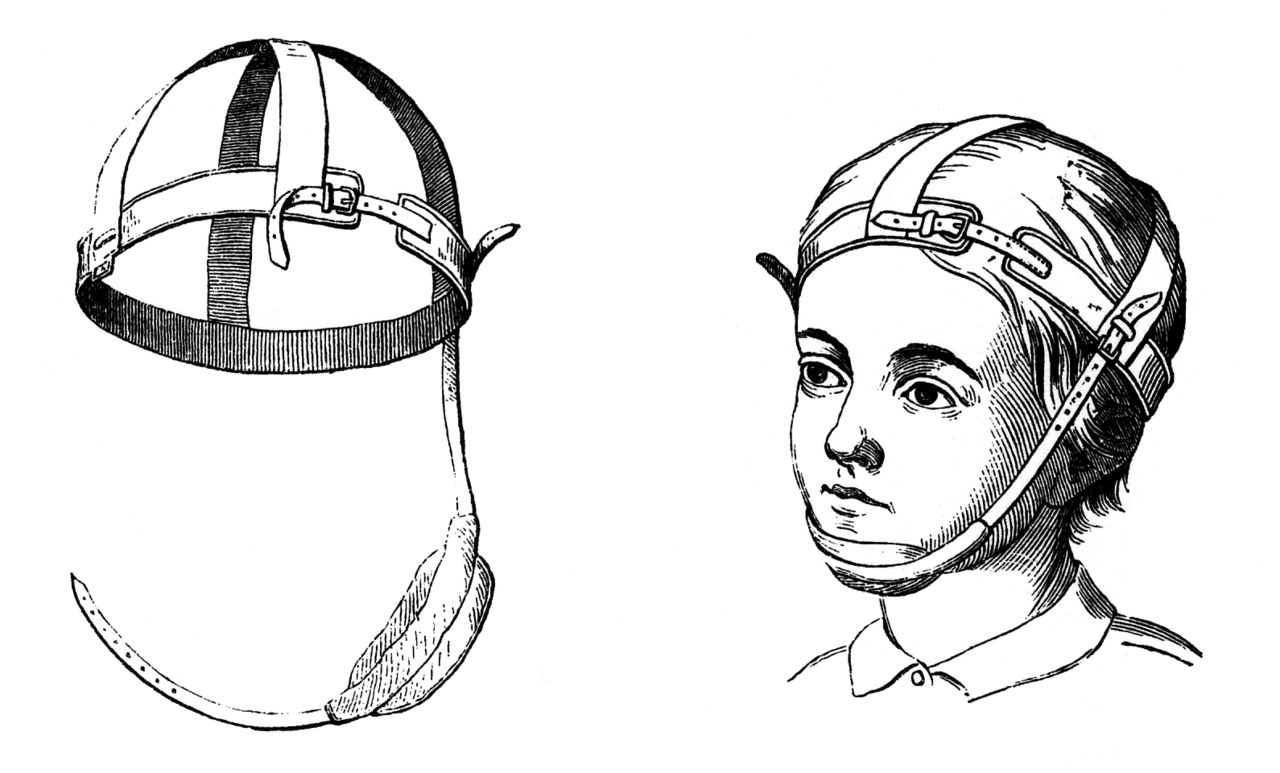

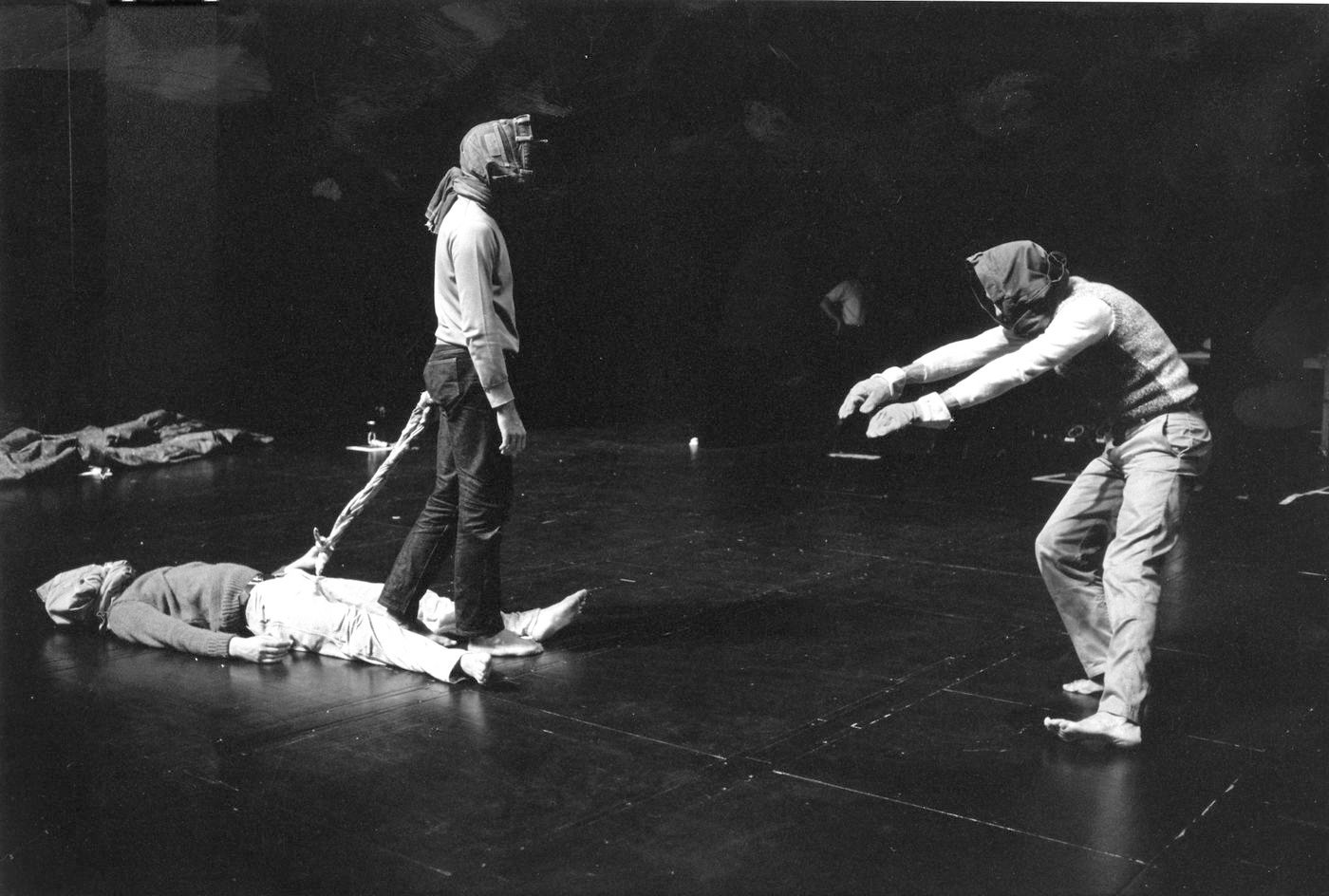

No, Duchamp, the nature of the objects, the absolutely impenetrable facade he could put up… I admired a lot. After I saw how many people were trying to put up fascinating but penetrable material. You know that? Or maybe it is that…like social Darwinism destroys Darwinism itself in some ways or interprets it to its own. So, popular art theory is very destructive of real artistic memes, and so that's what I liked about many of Duchamp’s work - the Big Glass I've seen many times, [and] that last work of the…that you look through the hole in the door into a 3D construct that he was secretly working on in his last years. And right into Boris [Charmatz]'s work that we were talking about. What is it?

Con forts fleuve by Boris Charmatz (1999), ©Jean-Michel Cima.

Con forts fleuve by Boris Charmatz premiered the 7th of October 1999 at the Quartz, Centre National Dramatique et Chorégraphique in Brest. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Con forts fleuve.8

Steve Paxton Con forts fleuve… Impenetrable. I mean, I penetrated it. I went home and thought it through and made…

Myriam Van Imschoot …an inferno.

Steve Paxton An inferno, yeah, I made a… Definitely. I saw a Dantean influence there, and I thought, “Well, this is just about right for a bright young guy to do," you know, to work with The Inferno or take that, you know, something that nobody else is dealing with at all these days. You don’t see, it’s not currently on our art calendars very much. Yeah, that's, that's he… Somebody ought to do that if they’re looking to make a work. Or it might influence them in just the right way in the way that Muybridge influenced me about, you know, long after my assimilation of him. Suddenly, I was… Anyway, I quite like those things, but I, yeah, I first questioned myself whether I should try to make an interpretation, you know, whether I should just wait. I was afraid I wouldn't know Boris that well. Now I feel like I’m going to know him better, but at that time, I didn’t know him very well, and it was, it was shockingly impenetrable in the first experience of it. I just was floored by an act of an action which was…in which it was so difficult to assign meaning, anywhere. Not in the continuity, not in the movement, none of the, you know…this thing falling down from above. This giant construction, you know, where the cloths are released. What a wild idea! What does it mean? I don't know what it means. Why are there so many of them? I don’t know why there are so many of them. I don’t know anything except that, you know, cloth falls from the heavens or something [incomprehensible]. I don't know… And the dancers. And I sort of very much like it on that level - as an impenetrable object, as opposed to the interpretable thing that I made of it.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s funny that you are so concerned with the meaning of that.

Ash1:08:24

Ash by Steve Paxton premiered in 1997 at deSingel in Antwerp, Belgium. ↩

Steve Paxton I'm only concerned in the way that I’m interested in the way the subconscious works. You see, because I had had… Well, with Ash9, I had a very big dose of my own subconscious working. Here is a work done on my father's death, written by me almost immediately after he died, trying to remember all the details, cause I thought it was such a fascinating event, you know. What I saw of consciousness, what I saw of him fading.

[end of minidisk, new minidisk is put in the machine and the interview continues]

And as I reached toward his face, I suddenly realized I was seeing death’s head, a skull. It was perfect, you know. The skin was so tightly pulled across his bones. He’d lost so much weight that it was very little flesh there, and the light was just right, and I was looking at my father and seeing this archetypical, you know, death…

Myriam Van Imschoot Cavity, skull, vanitas.

Steve Paxton Yeah, vanitas. Yeah, exactly that, with its hood and side. So, then I went to make this piece. I had told Antwerp that I was going to make a new solo, and I thought, well, I’ll just improvise something. I think that’s what I said to them, to make a new dance and just get some music, but I didn't do anything, and suddenly, I was within a month of having this premiere, and I hadn't done anything, and I started working like crazy, of course, you know. And I didn’t like anything I was doing. And then I thought, well, kind of in the back of my mind, I can always use that writing I did. One of the reasons that I became interested in it was it was such a good story that I had lived through. Usually, I don’t feel like my life is about stories, you know, nothing with an ending, nothing with a climax. So, I started thinking I could make a tape of that and dance to my own words about this experience that I had and I wrote about and that would be something I hadn’t done before. And it went on this way until the week before the premiere was due. And I’m going crazy trying to get out of the farm, you know, packing and trying to figure out what I was going to do and feeling terrible. And so I went to the computer to get the text, and it was there, but it wouldn’t turn into text. I didn't know what to do to make a text. I'm not very computer illiterate, but I’m, you know…. I had taken it from the IBM on which I wrote it and put into an Apple and the Apple…I didn't know how to translate it, essentially, and Lisa was in Australia! So, I called her, and she said she knew what to do, and she talked me through. It was the middle of the night in Australia. She was sitting there in this freezing office calling me, in her coat, in the darkness and telling me step by step. She was just brilliant. I mean, she talked me through all the computer stuff.

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh!

Steve Paxton Just as though she was there and got it to the point where the text was on the screen. And she said, Now, don't do anything else. Print it, print it from the screen just the way it is because when you try to save it, it’s not in a saveable form yet. So, if you try to save it, it will disappear again. It had taken us like half an hour transworld telephone to get to that stage, so I printed it and got it, and then, the next day, I left. And I had arranged…I said to the people in Antwerp, I need to record a text the minute I arrive. I was about a week early probably for the show. I got there on the weekend, I think. And in the same building where the theater is, there is a radio station. So, they had studios and technicians, and it was very easy to do. I read it through once, and that became the text. I thought I was going to make a 20-minute dance, and it was 35 minutes because I realized that I needed to speak very slowly and clearly for non-…people for whom English is not the first language. So, it took much longer to read it than I thought. Anyway, and then the lighting started.

Myriam Van Imschoot And then you told that making a piece is just…

Steve Paxton …that story.

Myriam Van Imschoot Just trying to answer the technician.

Steve Paxton Yeah, trying to answer this, this technician, who was not going to observe any of my normal methods in making work, you know, where it doesn't matter particularly when lights change because I'm so flexible as a dancer that I can go where there's light or leave light when I want to. You don’t have to change the light so much as let me change the space and design how lit I want to be. So he wasn't going to handle this, have this at all. And he was very close to quitting, but the older technicians there, you know, would come along and talk to him in Flemish, and he would calm down again. And finally, I realized I was sitting too far from him, and I went and sat right beside him, and then things… I was sitting back, so I could see the light. He was sitting down where the lighting board was, and yeah, we solved our problems. But what I made for the light [blows his nose] was a path through the space, a V-shaped path to the back of the stage, in the center of it, back up to the side, put a chair in the front, and on that chair — I ended up using it to pantomime an airplane and being in an airplane and throwing my father's ashes out of an airplane for the end. And then the very ending of it, after all this, on the one hand, a narrative about a man's death, on the other hand, very non-narrative dancing, absolutely nothing to do, but a person on a path, you know, a path which keeps being illuminated as you go - symbolic of a life or a something. In this case, symbolic of the story I was in, I suppose, in various ways. Then, it turned at the end into a kind of Judy Garland moment, where I was…the story ends with a poem that I had written, and I lip-synced my own voice. So that in the last moment, I was completely inside the theatrical image of myself being in the story. So that was very, very pleasing, but I didn't do this consciously. If I had done it consciously, well, I would have been pleased to have the thought, but what I did was…I did it unconsciously, so I am still pleased to have the thought, but I didn't have the conscious thought that made that piece. That piece was, you know, I can now interpret what happened to me in the making of it and how all these decisions came about and how the stress, what the stress was all about, the kind of pressure I put on the poor subconscious to have to make the piece while my consciousness was flubbing around.

Impenetrable1:16:11

So anyway, I look at Boris’s work, and I think, Well, whatever he thinks of his work, he may not… I mean, I’m now 60, right, so I have a lot more…I’ve interpreted myself many more times than he has. He’s quite younger. I don’t know whether he’s ready to do that work or not. Maybe that’s something to do in your forties or fifties, kind of thing. See yourself. He’s still in that first run of accepting who he is and coming to his identity, so maybe he doesn’t know how to answer these questions I’m asking, but his subconscious made that happen, for sure, even if he consciously has welded it, his subconscious was there working, so I can… Do I want to interpret this, or do I want to let it just be in an aesthetic blank like those Duchamp works? Duchamp, I think, was working consciously to make something that was impenetrable. I don't think he made those works in the same way that I made Ash or in the way I assume Boris made Con forts fleuve.

Myriam Van Imschoot I think so, too.

Steve Paxton I think he’s looking at it theoretically and

structurally, rather than…

Myriam Van Imschoot I mean, that’s what his writings…

Steve Paxton …indicate, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot At the time, it was indicating pretty much trying to…oh yeah… Although he had some interesting subconscious, subconscious when he was having those [optical] discs with…

Steve Paxton Yes, yeah.

Marcel Duchamp,Rotoreliefs, 1935. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot …images on10. And that was, I think, the work that he came closest to exploring subconscious visuals and stuff like that, but it’s very unknown work to many people.

Steve Paxton But we knew about it in the 60s.

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh, really?

Steve Paxton Oh, yeah. He was very popular among those artists - Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, Newman, de Kooning, Kline, they all…

Myriam Van Imschoot So you knew about the discs?

Marcel Duchamp, La Boîte-en-Valise, 1936-1941. ↩

Steve Paxton The discs you could find. There was a box that he made.11

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton And in the box were versions, reproductions of his work, including the Big Glass was in there. But the discs were there, as well. So, there was like a little museum in a box of his work, retrospective.

Myriam Van Imschoot Have you ever met him?

Steve Paxton Yes.

Myriam Van Imschoot Because he came on stage after Walkaround…about…?

Steve Paxton Walk…Walk…

Myriam Van Imschoot Walkabout…

Steve Paxton Walkabout Time, yeah…something like that.

Merce Cunningham, Walkaround Time, 1968. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Walkabout Time, yeah, but did you ever meet him?12

Steve Paxton Well, I didn't meet him at that time because I had left the company, but I had met him earlier.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, yeah. He’s an amazing artist. I just love reading about him.

Steve Paxton Yeah. Yeah, he made a great conceptual leap and left everybody else in the dust in a way. And yet at the same time, he's not very useful to the public except as a clown, you know. They look at the urinal and they say, “Wah Wah Wah Wah,” you know?

Myriam Van Imschoot The thing was, like, I want us to round up a little bit on this issue. It’s not to round up, no, but just…

Steve Paxton Just another hour left? [laughing]

The impersonations of Vincent Dunoyer1:19:37

In 1997, 3 Solos for Vincent Dunoyer, a Rosas production, premiered at the Spring Dance Festival in Utrecht, Holland. The evening consisted of three solos, danced by Vincent Dunoyer and choreographed by three different artists, i.e., The Wooster Group (Dances with TV and Mic), Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (Solo for Vincent) and Steve Paxton (Carbon). ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot There's a lot of interest in performance theory. There's a lot of interest in psychoanalysis. Not anymore in a way it would have been done in the 30s again or like in the 40s or 50s so much, about, you know, all the Oedipal relations and… So there's…it's very much alive in my…in my academic surroundings, but I never felt very inclined in using it myself although it's intriguing; and there's some very good analysis and very good stuff around. But there's like one single exception and that would have been, if I'm thinking, thinking about the piece of Vincent Dunoyer when he’s doing Carbon13. That’s the piece where I think that psychoanalysis could make, could make a lot of sense.

Steve Paxton Really? Why?

Myriam Van Imschoot Because it's very much about impersonation, impersonating…

Steve Paxton In the way that dance has always impersonated. We made it, actually, between video and my example in a very conventional way. Why is this suddenly…

Myriam Van Imschoot And also, I think, I talked about it later, that this is this whole thing apparently that he… When he saw you as a dancer first, that was like a big shock in terms of recognition of…

Steve Paxton The same. I for him.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton I totally saw my body on stage the first time I saw him on stage.

Myriam Van Imschoot Like, that’s my body?

Steve Paxton It was scary.

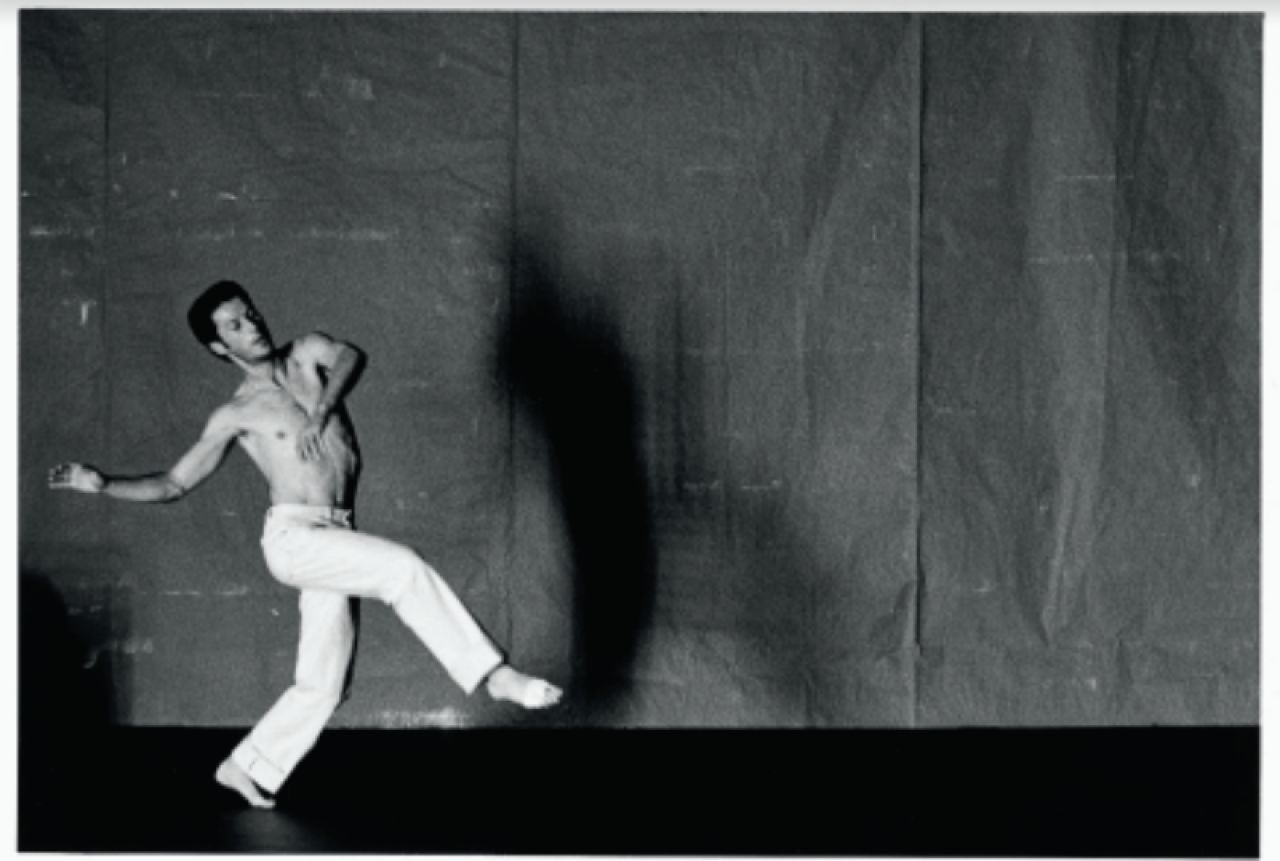

Vincent Dunoyer in Carbon by Steve Paxton, 3 Solos for Vincent Dunoyer, 1997, Rosas, ©Herman Sorgeloos.

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s my body.

Steve Paxton Or, it was unusual, anyway. It was startling. Did he feel the same?

Myriam Van Imschoot He felt very spelled, like, a very uncomfortable, you know…your body on stage by someone else.

Steve Paxton I know. I know.

Myriam Van Imschoot I mean, it’s just not a daily experience.

Steve Paxton We’re not, actually, that much alike, you know, but when you put, when you isolate us on stage, you don't know how, you know, you can’t… I mean, he’s a bit shorter than I am, and he’s actually a much finer-boned person.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton But yeah, there is just… Maybe it’s the proportions or something that carry the idea. Yeah, the first time I saw him, I… Lisa and I were together watching a piece of Anne Teresa [De Keersmaeker]’s, and it was very clear to both of us what we were seeing, and Lisa was sure that she had gotten a tape of me dancing and had him learn the movement. That was the way she explained it. And then, I quickly learned that that wasn't the case. I think he made that movement, in fact, in the solo that I’m thinking of now, you know, where he’s got his back to the audience. He’s upstage left, or he’s upstage right, audience left, with his back to the audience, and I think he has his shirt off. We see a back, or maybe I’m remembering him…

Myriam Van Imschoot That was in a piece of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker?

Steve Paxton Yeah, the one with the sloped floor and the…was it a pianist? A live…

The piece that Paxton refers to is not Achterland (1990) by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, but Toccata, which premiered on the 27th of June 1993 in Amsterdam. The piece was danced and created together with Marion Ballester, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Vincent Dunoyer, Fumiyo Ikeda, Marion Levy and Johanne Saunier. Bach’s music was performed live by pianist Jos Van Immerseel. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah! That’s Achterland.14

Steve Paxton Yes.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. Oh. Interesting. Well, he had a similar…

Steve Paxton …response as I did.

Myriam Van Imschoot Response. And I think that somehow he went for, for what, what frightened him in that.

Steve Paxton The Mary Fulkerson theory again here.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. Also this thing of, you know, the confusion of identities when you see an echo of your body, and that he wanted to identify as much as possible with the alter ego. And it's very much an exercise in seeing how much you can become the other one by asking his movements, by having like a vivisection of it.

Steve Paxton But actually, I think he was less like me in…

Myriam Van Imschoot In that piece!

Steve Paxton …in Carbon than he did in Achterland. For some reason, Achterland seemed to have the…

Myriam Van Imschoot It had more of it.

Steve Paxton That’s where I saw the similarity. And when I saw Carbon, I lost it. I didn't anymore see it.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, maybe because it became…

Steve Paxton I don't know.

Myriam Van Imschoot If it comes closer, you see more the differences... [simultaneously]

Steve Paxton …the differences. [simultaneously]

Myriam Van Imschoot ...again. The whole subtext underlying that, too, I mean, is if you put like, in terms of a father to a son, I mean, he’s attributing you in that position.

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot I mean, it’s not, but still then, it’s about… It’s a kind of erasure even of someone if you become this person so fully as possible, you know, it's, it's very much it's very…

Steve Paxton There are a lot of possible interpretations, psychological interpretations.

Myriam Van Imschoot So, it’s the first time I thought, well, here, it

Steve Paxton Yeah, but I mean, essentially, aside from the resemblance that we might have to each other, it's a very typical and usual relationship of the dancer to the choreographer that we had. And so, we would be… In this particular instance, it seems very applicable to a kind of analytic mode…both for his motivation, especially for his motivation, but we both had recognized it, apparently. But I mean, it's the same thing that I did with Cunningham, you know, somebody that I don't look at all like, but there was something alike, there's something…actually, something that I wanted to learn to be like. It was more like that. So, it was even more nascent.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton It wasn't fully developed.

Myriam Van Imschoot No.

Steve Paxton But I developed it, and I got so I could do his movement, you know, very, very clearly — Cunningham-esque stuff. Training every day, lots and lots of rehearsal, but one can get there. One can change oneself into the person that is your exemplar. So, it’d be very interesting to take whatever you got out of the Steve and Vincent relationship and then apply it more broadly because it’s…

Myriam Van Imschoot …to the Merce Cunningham…

Steve Paxton Well, to…

Myriam Van Imschoot Just, in general.

Steve Paxton …to the global dance relationship of the choreographer to the dancers. Because I mean, you do it with men, you do it with women, you're learning something that you could not do because somebody else has originated it, but you can learn to do it, you know, through time, so close enough.

Myriam Van Imschoot But it’s very telling, I mean, it's probably part of every, every dance training technique. It's in it. It’s innate.

Steve Paxton Yeah. Innate.

Myriam Van Imschoot But for Vincent, even in an extreme way, because he's a dancer who has struck me as a Xerox machine.

Steve Paxton He's a reproducer.

Myriam Van Imschoot He's a very good reproducer. He’s a replicator. And he made it a wonderful skill in replicating, and it's developed that it’s, it's pushed to its excess, you know, even if everyone does it as a training technique to learn some influence or grow familiar with certain aesthetics. He, he is a copy…a copy machine. And his whole evening, the three solos, are about copying.

Steve Paxton Yes. I read that book that he's made.

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh, he made a book?

Hugo Haeghens (ed.), The Memory of the Look, Dans in Limburg, 2000. ↩

Steve Paxton The little red book.15

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh, yeah. Yes, yes! I haven’t read the text yet.

Steve Paxton Oh, it has an excellent text on this issue, essentially, him as a replicator and how he’s using it as a means to hang dance ideas, performance ideas on. He’s very much into this idea himself.

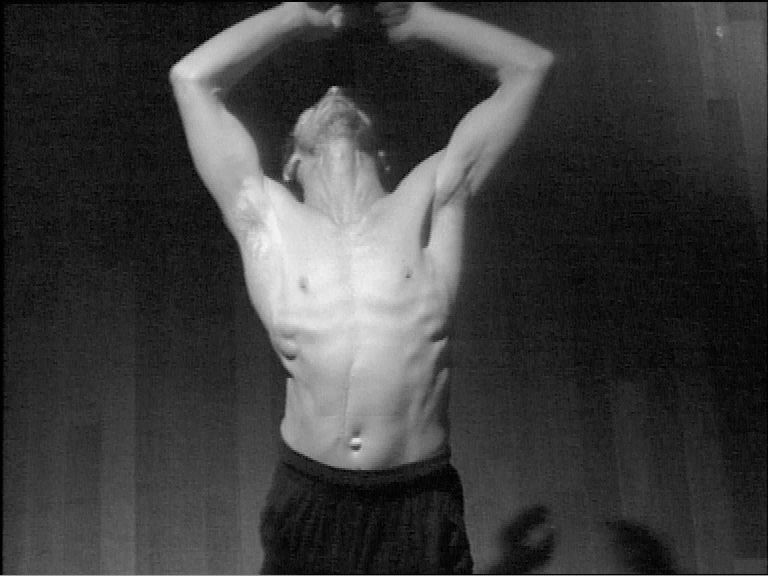

Myriam Van Imschoot And the thing with replicating Steve Paxton is that he’s…he was very clever in taking into account the fact that you're also mediated in, for example, he’s bare-chested, which you’re usually not when you're performing, but you were in the video of Walter Verdin.

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Walter Verdin, Goldberg Variations 1-15 & 16-30, 1992, ©Walter Verdin.

Myriam Van Imschoot Which is probably what most of us…

Steve Paxton …people see. Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot …see. So he, he replicates you from a mediated film device and the same with the recording of Glen Gould. He's replicating the humming, but from, you know, from a recording.

Steve Paxton Yeah, as though from…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, so it's, it's really also playing with immediacy and immediate incorporation and mediated incorporation. Yeah, something like that in other words… not very articulate.

Steve Paxton No, no, no, you’ve been very articulate. It's just very general because it is such a big idea.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton We don't have another example of this.

Myriam Van Imschoot But it struck me that he was bare-chested. I said, he, the… When we speak of Steve Paxton as an image, the image…

Steve Paxton Teacher. [laughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot …is very much a mediated one by film, so it would be a bare-chested Steve Paxton even though it may have been the first…

Goldberg Variations 1-15 & 16-30 (1992) is a dance film made by Belgian artist Walter Verdin. Verdin filmed Paxton improvising to the Goldberg Variations by J.S. Bach and recorded by Glenn Gould, an improvised dance he has performed between 1986 and 1992. The recordings took place in the Felix Meritis building in Amsterdam. ↩

Steve Paxton Yeah, he did the Goldberg…16

Myriam Van Imschoot The first time you are, or one of the few times you were [bare-chested].

Steve Paxton Yeah, the first time, I think.

Myriam Van Imschoot He replicates images, also.

Steve Paxton Versions. I saw it as having very complex costuming at the beginning and gradually lightening up and becoming less and less a theatrical performance and gradually down to just a very relaxed presentation.

Myriam Van Imschoot [laughing]

Steve Paxton Because there was the issue of the clothes. Like, we find him after he leaves the stage, after the Wooster piece, then the curtain moves, and it gets to the other end of the stage just as he's finishing dressing for the next piece. I loved that little touch, and then, so the undressing for the next piece was very logical, and I didn't think it was mediation, of course, but it’s possible.

Myriam Van Imschoot Interesting. Steve, I think we have to call it an end for today.

Steve Paxton Okay.

Myriam Van Imschoot You’re…you have to get ready.

Steve Paxton Yes, I’ll have to go find a taxi and go up to P.A.R.T.S.

-

Robert Rauschenberg used the term “combine” to indicate a series of works that combined aspects of both sculpture and painting. Minutiae (1954) was one such combine, which also appeared as a set for the eponymous piece by Merce Cunningham. ↩

-

Satisfyin Lover (1967) is a choreography by Steve Paxton in which 42 people cross the stage from stage left to stage right. ↩

-

White Oak Dance Project was a dance company founded in 1990 by Mikhail Baryshnikov and Mark Morris. In 2000, White Oak Dance Project revived both Paxton’s Satisfyin Lover (1967) and Flat (1964). ↩

-

The choreography by Lucinda Childs, here referred to as City Dance, is actually called Street Dance (1964). Street Dance was the result of an exercise Robert Dunn gave his workshop participants, i.e. to make a dance that lasts six minutes. The audience looked down from an apartment onto the streets where the performers, who blended with the passers-by, would draw attention to certain architectural features of the surrounding buildings. ↩

-

The name of the Russian count is Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin. ↩

-

The piece directed by Paxton was called 1894 and was performed in 1984 at Dartington College. Some years later, in 1986, Paxton and Kilcoyne founded Touchdown Dance, an initiative to teach Contact Improvisation to people with a visual impairment. ↩

-

The standing still is often referred to as the Small Dance. It first appeared as the last five minutes of Magnesium (1972), in which the performers, after a very intense dance, stand still. For a description of the small dance, have a look at the interview Practices of Inclusion (2019). ↩

-

Con forts fleuve by Boris Charmatz premiered the 7th of October 1999 at the Quartz, Centre National Dramatique et Chorégraphique in Brest. ↩

-

Ash by Steve Paxton premiered in 1997 at deSingel in Antwerp, Belgium. ↩

-

Marcel Duchamp,Rotoreliefs, 1935. ↩

-

Marcel Duchamp, La Boîte-en-Valise, 1936-1941. ↩

-

Merce Cunningham, Walkaround Time, 1968. ↩

-

In 1997, 3 Solos for Vincent Dunoyer, a Rosas production, premiered at the Spring Dance Festival in Utrecht, Holland. The evening consisted of three solos, danced by Vincent Dunoyer and choreographed by three different artists, i.e., The Wooster Group (Dances with TV and Mic), Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (Solo for Vincent) and Steve Paxton (Carbon). ↩

-

The piece that Paxton refers to is not Achterland (1990) by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, but Toccata, which premiered on the 27th of June 1993 in Amsterdam. The piece was danced and created together with Marion Ballester, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Vincent Dunoyer, Fumiyo Ikeda, Marion Levy and Johanne Saunier. Bach’s music was performed live by pianist Jos Van Immerseel. ↩

-

Hugo Haeghens (ed.), The Memory of the Look, Dans in Limburg, 2000. ↩

-

Goldberg Variations 1-15 & 16-30 (1992) is a dance film made by Belgian artist Walter Verdin. Verdin filmed Paxton improvising to the Goldberg Variations by J.S. Bach and recorded by Glenn Gould, an improvised dance he has performed between 1986 and 1992. The recordings took place in the Felix Meritis building in Amsterdam. ↩

-

Sigmund Freud, The Schreber Case, 1911. ↩

-

Leonard Shengold, Soul Murder: The Effects of Childhood Abuse and Deprivation, Ballantine Books, 1989. ↩